Two years after the Nigerian Civil War ended in 1972, former military Head of State Yakubu Gowon decided that Nigeria’s civil service needed to be repositioned to deal with the challenges of managing a nouveau riche country. Swimming in petrodollars at the peak of the oil boom in what was and is still by some distance Nigeria’s most successful ever decade, Gowon famously remarked that Nigeria’s problem was not how to make money, but how to spend it.

While that comment is often characterised as a mission statement for the spendthrift profligacy that would soon come to define Nigerian governance, what Gowon actually meant was that Nigeria was in a unique situation to achieve an unprecedented level of development for an African country due to its newfound petro wealth, and the challenge was how to direct that spending in such a way as to feed that development. Gowon turned to Jerome Udoji, a distinguished career civil servant to lead a commission that would create and administer a new strategy to help the Nigerian civil service assume a new role at the centre of Africa’s most promising economy in the 20th century.

Jerome Udoji – The Original Stephen Oronsaye

Set up in 1972, the Udoji Commission’s remit was wide and far ranging including creating training systems and global peer observation for civil servants, creating an integrated administrative structure to better fit the centralised system of government hurriedly instituted 6 years earlier by Aguiyi Ironsi, eliminating inefficient departments and waste, and introducing a new civil service management doctrine that put objective and accomplishment over process and bureaucracy. This all sounded great on paper and it would have been a watershed moment in Nigeria’s corporate history were it not for two subsequent details that changed everything.

The first is that the final objective of the Udoji Commission – upward review of civil service and armed forces remuneration – soon subsumed every other accomplishment of the commission. Instead of creating a new civil service that was repositioned and freshly incentivised to achieve maximum productivity, the posturing of the Gowon administration gave Nigerian public servants the idea that the good times were rolling and the government was here to give everyone a share of the “national cake.” Indeed to this day, few people actually remember what the Udoji Commission was. It is only remembered now as the “Udoji Award,” which is how the (often exponential) salary increases infamously came to be known.

This high octane “roaring 70s” atmosphere fed by oil-fuelled expenditure and the subsequent rapid growth of middle class consumptive capacity led by the civil service was even captured in the popular music of the time, encapsulated by Fela’s playful, high energy 1972 track ‘Eko Ile.’

Unfortunately, amidst all this government expenditure-fuelled merrymaking, Nigeria’s actual productive base to support a rapidly expanding population was not growing. An unprecedented number of Nigerians were accessing secondary and higher education and tens of thousands of new graduates were joining the workforce every year without a commensurate economy to support this growth. Successive governments between the early and late 1970s then did what every Nigerian government does when it is flush with cash – they expanded the civil service. Udoji’s changes regarding efficiency and reduced waste were quietly undermined one after the other, leaving just one legacy from his commission unchanged by the time Murtala Mohammed seized power in 1975 – the Udoji Award.

Another Set of Reforms Become Necessary – Enter Oronsaye

The second event that completely defeated the purpose of the Udoji Commission was one of the signature policies that marked the chaotic 198 days that Mohammed spent in office. Roughly 10,000 civil servants saw themselves suddenly tossed out of office – often without compensation or pensions – at the fiat order of Mohammed based on arbitrarily designated standards regarding age, health, competence and alleged wrongdoing. Overnight, from being the best regarded and most desirable middle class profession in Nigeria, the civil service degenerated into an everyday scramble for sustenance between desperate people in an unstable, insecure environment that was liable to change at a moment’s notice depending on what side of the bed the Head of State woke up on.

Mohammed lasted just 198 days in office before the violent 1976 coup by Lt. Col. Buka Suka Dimka brought in Olusegun Obasanjo, followed by Nigeria’s first postwar attempt at democratic rule under Shehu Shagari. Regardless of his short stint, this destructive legacy outlived him and survives to this day. The combined effect of the Gowon and Mohammed regimes was that public service in Nigeria retained the negative pull of Gowon’s ‘Udoji Award’-style national cake distribution and combined this with the negative push factor of the grasping, desperate, ad hoc culture instituted by General Mohammed’s knee-jerk civil service and armed forces purge to create the toxic governance atmosphere we are all too familiar with nowadays.

Nigerian politicians and senior civil servants learned to create vast amounts of wealth for themselves by exploiting the inherent efficiencies and leakages in creating layer upon layer of ad hoc institutions – often by military fiat – and using them as their oil rent-funded pork barrel enterprises. In 2014, President Goodluck Jonathan – himself the beneficiary of a period of high commodity prices and a resultant economic boom period – turned to a career Accountant-turned civil servant to do what Jerome Udoji should have done 42 years before.

Stephen Oronsaye was a hard nosed public administrator who had earned his stripes under Olusegun Obasanjo and Umaru Yar’adua, fighting – and ultimately prevailing over – senior civil servants who resisted his attempts to introduce 8-year tenure limits for directors and permanent secretaries in the federal civil service. He was given the remit to chair a committee that would create a comprehensive roadmap for rationalising and repositioning the central civil service to make it more productive and to eliminate 4 decades’ worth of military and civilian ‘national cake’ extraction enterprises disguised as government institutions. 6 years after he submitted his report and 5 years after Goodluck jonathan left power, the report is once again getting attention after being approved for implementation by President Muhammadu Buhari. So what can we actually expect from this report?

What is the Oronsaye Report and why is it a big deal?

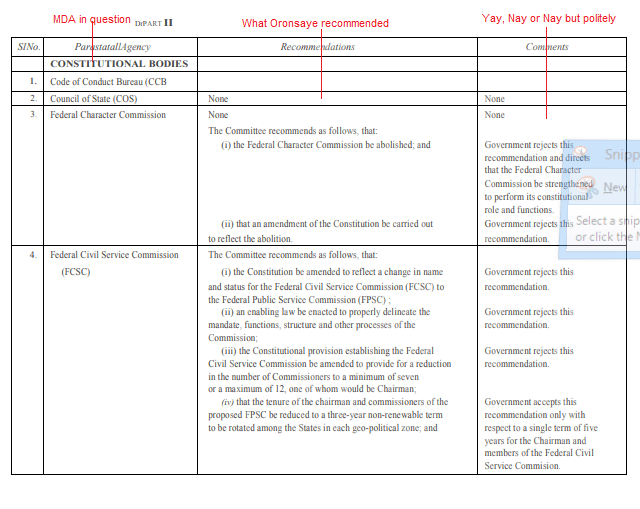

To cut a long and circuitous story short, what is commonly known as the ‘Oronsaye Report’ is a 103-page whitepaper on the report of the presidential committee inaugurated by Goodluck Jonathan to provide a framework for the restructuring and rationalization of the multitude of parastatals, ministries, commissions and agencies under the remit of Nigeria’s federal government. It is basically a document that tells the government what bodies do not need to exist, what bodies should be merged for maximum efficiency and what functions are being duplicated or contested in such a way as to make governance inefficient, slow or unjustifiably expensive.

In general terms, it is helpful to think of it as the report submitted by an external systems auditor hired to observe the inner workings of an organisation and find out how to make it work in a leaner and more efficient manner. Or at least that is what it should be on paper. In reality, the situation -as with that of any document that aims to reduce the size of government in Nigeria – is not that straightforward. I mentioned earlier that Stephen Oronsaye faced severe opposition while trying to implement age-based tenure limits for parastatal heads under Umaru Musa Yar’adua. This is the tip of the iceberg of pushback that his report received and continues to receive.

The Oronsaye Report is a big deal for many reasons. Some see it as a key part of any Nigerian strategy to address the situation where roughly 70 percent of the federal budget is spent on wage payments and debt repayments annually, leaving roughly 30 percent for capital investment in a country that has an estimated $100 billion annual infrastructure financing gap. Making the leviathan-sized federal government smaller is seen as an inescapable part of addressing this imbalance.

On the other hand, some also see it as the document written by an arrogant, out of touch, free market fundamentalist that threatens to destroy their only tried and tested source of wealth creation over the past five decades in Nigeria – government expansion. The suggestion that the government should not be empowered to play an ever-expanding role in the Nigerian economy, or worse still that its share of the economy should be reduced makes this group of people bristle with outrage. The ethnic origins of its author and the president who commissioned him also add another political dimension to this statist view.

A third group of people see the report as an unworkable solution, but nevertheless a useful part of the conversation about repositioning the Nigerian civil service in line with repairing Nigeria’s economy to deliver the type of growth it needs to support nearly 200 million people without falling into chaos. So what promise exactly does this report hold and is it likely to do what it says on the tin?

Will the Oronsaye Report make the FG more efficient?

This is by no means a straightforward question to answer, mostly because the report itself is not by any means a cut and dried document ready to plug into the system and play. Indeed, as you go through the document line by line, it quickly becomes apparent that any proposed implementation will be a protracted affair that drags on for years instead of the weeks or months that some hope for. For one thing, approximately 90 percent of the recommendations in the original 800-page report were rejected out of hand by the government, which is indicated in the right margin where the government’s response is indicated in the whitepaper.

The phrase “Government rejects this recommendation” appears 266 times in the document. In contrast the phrase “Government accepts this recommendation” appears only 125 times. The phrase “Government notes this recommendation,” which is to say, “Government rejects this, but more politely,” appears 252 times. Reading through the whitepaper, there is no sense that any priority is actually given to the professional findings of Oronsaye’s committee. The government’s responses seem to indicate that the only priority is to ensure that it remains insulated from as much major change as possible, which of course is contrary to the spirit of fundamental change or repositioning.

This goes to the heart of what is wrong with the report or any intended implementation thereof. While those who are familiar with the structure of Nigeria’s annual federal budget are very used to the idea that a number of functions and associated expenditure are duplicated in several places, the political will to attack this duplication is another matter entirely. The issues and ideas examined in the report are not by any means rare or niche knowledge – I once even wrote a television script alongside my late friend late Binta Bhadmus on this very issue when we both worked on The Other News on Channels Television. None of this indicates that a government establishment that historically has no interest in making itself smaller and less powerful will suddenly see any benefit in doing so now, just because President Buhari said so.

And then there is the issue of the panel that will inevitably need to be set up to action it if it ever makes it that far. Nigeria’s civil service has never at any point in its history successfully carried out a cross-agency collaboration this wide-ranging, especially on a topic this politically charged and contentious. This is not to mention the possible issues surrounding permission from the National Assembly and even potential legal repeals that any implementation of this report might require.

So what exactly does President Buhari’s approval of the Oronsaye Report mean realistically, given these circumstances? Does the president’s approval mean the Oronsaye Report will be implemented even in part? Short answer: no. We have established that the report is by no means even a completed, cut-and-dried document, neither is the political will to implement it going to extend beyond the pages of newspapers once the actual operational realities of trying to trim 50 years of pork barrel come into stark relief. Ultimately, given the realities of Nigeria’s decades-old situation and the antecedents of the current administration, chances are that this latest “approval” will more likely than not end up being little more than another short-lived window dressing attempt.

Professional Analysis of a Development Expert

According to development and governance expert, Dr Chiwuike Uba, the decision for implementation of the report is coming too late, though President Buhari should be commended notwithstanding for even showing the political will to approve implementation of the report. In his words:

“Approval for the implementation of the Report is a desirable one, considering the would-be benefits, especially, now that the country is faced with many challenges, including COVID-19, dwindling revenue, rising public debt, over-bloated and non-committed public service, high poverty rate, inflation, debt service obligations, fiscal deficit and corruption. It would be difficult to implement most of the recommendations as they have been overtaken by time, especially as the government has created new Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs) after the report was submitted.

“The best approach would have been to review the structure of the public service and governance structure, in line with the current realities, policy, and economic thrust and revenue profile of the government to promote economic growth/development and sustainability, since who heads departments and units when Ministries and Agencies that are merged would be an issue to contend with.

“Implementing the report, as it is, would create both budget and legal issues on agencies created by law. In addition to creating biased political considerations in implementation, the merger of MDAs would create conflict; occasioned by bureaucracy and hierarchy in the civil service structure. Who heads departments and units when Ministries and Agencies are merged would be an issue to contend with. I am not sure the country is ready for the squabbles this would create in the end. The best approach would have been to review the structure of the public service and governance structure in line with the current realities, policy, and economic thrust and revenue profile of the government to promote economic growth/development and sustainability.

“In addition to having many MDAs that act as the conduit for theft and other forms of corruption, the civil service is overstaffed with alarming ghost workers; despite the government’s efforts to weed the system of ghost workers and that the civil/public service contributes immensely to the culture of corruption, cronyism, and foot-dragging. The high cost of servicing the public sector is averse to economic development and growth. The bloated bureaucracy representing just 1% of Nigeria’s population enjoys allowances amounting to over 35% of the total budget of the government; even when labour productivity in Nigeria is one of the lowest across the world.

“In addition to channeling money to be saved from rationalization (mergers and scrapping of MDAs and staff retrenchment) to building infrastructures, social sectors and support to start-ups and existing businesses, the lean government will improve the effectiveness, efficiency, accountability and transparency of government programs and systems as well as eliminate waste in governance and government systems.

“Internal and external challenges will naturally militate against the execution of President Buhari approval for the implementation, “as a result of the underlying political and financial considerations as well as the ‘powerful’ individuals occupying positions in some of the MDAs recommended being merged or scrapped”.

“Retrenching of staff comes with huge costs– severance pay, gratuity and pensions, resistance from the labour unions, and even costs associated with movements. More so, the government white paper disagreed with most of the recommendations made by the Oronsaye report. The big question should be: which of the reports has the President approved for its implementation?

“This clarification is necessary. Make no mistake, the white paper recommendations were mainly influenced by political considerations and I can assure you that those considerations are even stronger in Nigeria of today. We need to do more work; it does not need a knee jerk approach Nigeria is known for. It is a structural problem that needs clear and sustainable solutions. Do we still need the current governance system with over bloated and misaligned public service structure? We need a holistic approach that would not only redefine the structure of government institutions—executive, legislative and the judiciary but also how they operate to deliver services.”

You can read the full Oronsaye Report whitepaper here.

You may be interested

Iheanacho Thrilled To End Sevilla’s Goal Drought

Webby - October 31, 2024Super Eagles forward Kelechi Iheanacho is full of excitement after opening his goal account for LaLiga club Sevilla.Iheanacho netted a…

I’m Ready To Return To Football –Ranieri

Webby - October 31, 2024Former Cagliari manager Claudio Ranieri has expressed his desire to return to football.Ranieri, who stood down from Cagliari at the…

Do Libya Stand The Chance To Successfully Appeal CAF’s Decision Against Them?

Webby - October 31, 2024This video showcases the trending stories making the rounds over the weekend on Complete Sports, they are the Editors “Pick…

![American Pastor, David Wilson Seen Eating The Box Of Woman Who Isn’t His Wife [Video]](https://onlinenigeria.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/american-pastor-david-wilson-seen-eating-the-box-of-woman-who-isnt-his-wife-video-150x150.jpg)