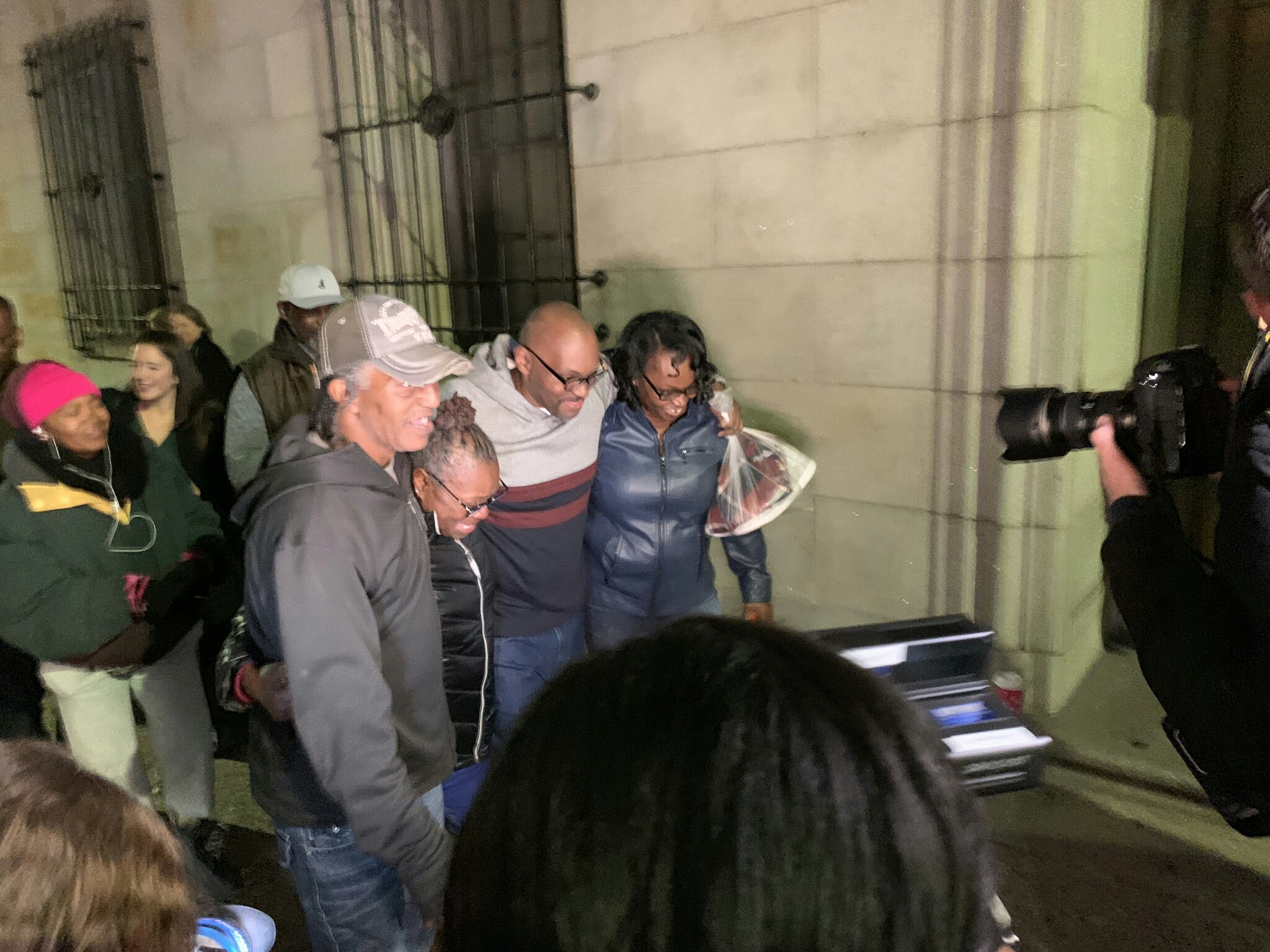

Alfred Chestnut, Ransom Watkins and Andrew Stewart were teenagers when they were sentenced to life in prison in 1984 for murdering a Baltimore teen. They were exonerated and released on Nov. 25.

The whole story

On Monday, 36 years after they were incarcerated, Baltimore Circuit Court Judge Charles J. Peters declared them innocent.

“On behalf of the criminal justice system, and I’m sure this means very little to you, I’m going to apologize,” Peters told them. “We’re adjourned.” The packed courtroom erupted in applause, and family members began crying and hugging.

The extraordinary exonerations were set in motion through the perseverance of one of the defendants, Alfred Chestnut, now 52, who never stopped pushing for a review of the case. This spring his claim was picked up by the Baltimore City state’s attorney’s office’s Conviction Integrity Unit, which uncovered a flawed case that prosecutors now say encouraged false witness testimony and ignored evidence of another assailant.

On Monday at 5:15 p.m., Chestnut and his childhood friends Ransom Watkins and Andrew Stewart walked out of the courthouse onto North Calvert Street as free men, into the arms of weeping mothers and sisters and fiancees who doubted they would see this day.

“This is overwhelming,” said Chestnut, surrounded by cameras, lawyers and family. “I always dreamed of this. My mom, this is what she’s been holding on to forever. To see her son come home.”

As the decades passed, two of the men gave up hope of ever seeing the outside world again. But Chestnut kept pushing. In May, he sent a handwritten letter to city prosecutor Marilyn Mosby’s office, after seeing her on television discussing the unit dedicated to uncovering wrongful convictions. Chestnut included new evidence he’d uncovered last year that incriminated the man authorities now say was the actual shooter. The Baltimore prosecutors dug in quickly, reviewed the case and re-interviewed witnesses.

The exonerations of Chestnut, Watkins and Stewart are the seventh, eighth and ninth enabled by Mosby’s Conviction Integrity Unit since she took office in 2015. Mosby visited each man in prison on Friday to give them the news she was asking for their freedom, a moment she called “surreal, incredibly powerful.” She said she told the men: “I’m sorry. The system failed them. They should have never had to see the inside of a jail cell. We will do everything in our power not only to release them, but to support them as they re-acclimate into society.”

Donald Kincaid, the lead detective on the case, was stunned to learn that the three men were being exonerated, and denied any improprieties with the Baltimore police investigation. “What would I get out of that?” Kincaid asked Monday. “You think for one minute I want to send three young boys to prison for the rest of their life … I didn’t know those boys. I didn’t know them from Adam. Why would I want to do something like that?”

Police reports produced soon after the killing revealed that numerous witnesses had told Baltimore investigators that Michael Willis, then 18, was the shooter, prosecutors now say. One student identified him immediately, one saw him run and discard a handgun as police pulled up to Harlem Park Junior High School, one heard him confess to the shooting, and one saw him wearing a Georgetown jacket that night.

But police, including Kincaid, focused on Chestnut and Watkins and Stewart, all 16, the Conviction Integrity Unit concluded. The three had skipped high school that morning and were goofing around in the hallways and classrooms of Harlem Park, visiting siblings and chatting with former teachers. Teachers and students saw them — and the teens admitted they’d been there. A Georgetown University jacket was later found in Chestnut’s bedroom.

“When I was in the crime scene up at the school,” Kincaid said, “three young girls approached me and told me who did it. I didn’t coerce them for nothing. They passed the information to me, that’s what opened up the case.” He did not remember Willis as a suspect and denied withholding any information. He said he had not spoken to the Conviction Integrity Unit, and said that Mosby was “trying to make every one of us [officers] look like liars and cheats. That’s crazy.”

The teens were kicked out around 12:45 p.m. by a security guard who testified at trial he lectured the boys about staying in school, watched them walk up the street away from the school, and then locked the school doors well before the 1:15 p.m. shooting of Duckett. Prosecutors at the time said the trio must have sneaked back in.

Defense attorneys pressed for evidence that cast doubt on their clients’ guilt. In 1984, then-Assistant State’s Attorney Jonathan Shoup told the court the state had no such reports, despite the fact there were police documents showing that the trial witnesses had twice failed to identify the three defendants in photo lineups as well as statements implicating Willis. A judge sealed the reports. Then, when Chestnut made a public records request to the Maryland attorney general last year, the office turned them over.

“It made me angry,” Chestnut said. “Just the fact that everything was concealed all those years. I knew that they didn’t want to reveal those things.”

Mosby said the case raised a number of problems she intends to address. The teen witnesses were repeatedly questioned without their parents present, she said, and they felt pressured to falsely identify Chestnut, Watkins and Stewart. Mosby is seeking laws to prohibit such questioning by police without a parent, guardian or lawyer.

Maryland also has no working system to compensate exonerees even though such payments are allowed by state law; the government for years has lagged behind other states in making such payments. After months of pressure from advocates and dozens of lawmakers, Gov. Larry Hogan (R) and the Maryland Board of Public Works recently initiated a process to pay $9 million to five exonerees who collectively served more than 120 years in prison for crimes they did not commit. Mosby said she will lobby for a formalized compensation process for all exonerees. The three men in this case declined to comment on whether they would seek money for their wrongful convictions.

And Mosby said there is no support system for those who walk out of prison after years or decades inside. She has created a Resurrection After Exoneration program to connect exonerees with mental and physical health services, education, housing and job opportunities. “I think it’s important and incumbent on us,” Mosby said, “as the system that has wronged them, to be able to take accountability. We’re excited to show that we’re going to support them.”

Mosby’s Conviction Integrity Unit worked closely with the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project, which Executive Director Shawn Armbrust said had acquired a federal grant allowing the prosecutors to hire a full-time investigator who helped track down witnesses in this case. She said actual-innocence cases where prosecutors work together with defense attorneys typically take about a year, and when the cases are contested they take more than seven years.

When Mosby’s office realized there was a possibility of actual innocence, they arranged for the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project and other lawyers to represent the men. The Maryland Office of the Public Defender and the University of Baltimore Innocence Project Clinic represented Chestnut, the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project and Christopher Nieto represented Watkins, and Booth Ripke and Rachel Wilson represented Stewart.

About 50 prosecutors across the country have launched Conviction Integrity Units to review old cases. Philadelphia’s unit has exonerated 10 murder defendants since last year. Armbrust said the teen defendants in this case “would never have gotten out without a Conviction Integrity Unit. Nobody could believe multiple witnesses would lie about the same event. You just have to wonder about how many cases there are in places where prosecutors aren’t willing to take a serious look at claims of innocence.”

The main players in the conviction of the three men are gone from the justice system. Kincaid, who was featured in the book “Homicide” by David Simon, retired from the Baltimore police in 1990. He said he did not coerce the witnesses to incriminate the three defendants. “No. Come on, no. Hell no,” Kincaid said.

Willis, who had a number of arrests on drug and assault charges after the Duckett slaying, was shot to death in West Baltimore in 2002 at age 37.

All three defendants always maintained their innocence, and Watkins’s insistence that he was not involved in the killing was captured by Simon while Simon was trailing Kincaid at the Maryland Penitentiary in July 1988. There, Kincaid encountered Watkins, according to Simon’s book. Watkins was 21 and already had been behind bars for nearly five years.

“You remember me, detective?” Watkins said to Kincaid, according to Simon.

“I remember you,” Kincaid replied.

“If you remember who I am, then how the hell do you sleep at night?” Watkins asked the detective, who was there investigating an unrelated prison riot.

“I sleep pretty good,” Simon reported Kincaid saying. “How do you sleep?”

“How do you think I sleep?” Watkins responded. “How do I sleep when you put me here for something I didn’t do?”

“You did it,” Kincaid shot back.

“The hell I did,” Watkins told him. “You lied then and you lyin’ now.”

In addition to being included in Simon’s award-winning book, published in 1991, the scene was re-created almost verbatim in a 1996 episode of the TV series “Homicide: Life on the Street,” Watkins’s attorneys said.

“At 16 years old, they threw me in a prison among a bunch of animals,” Watkins, now 52, said in a phone interview Sunday. “The things I had to go through, it was torture. There’s no other way to describe it.”

The three men were together in the Maryland Penitentiary for 12 years before being split up. “We held on to each other,” Watkins said. “That’s what got us through this journey, when we needed each other.”

Stewart, now 53, said his arrest and conviction destroyed his life, and many of his family members died while he was in prison. But after two decades behind bars, he came to accept “the significance of faith and the value of God.” He has been teaching Bible class in prison, and said one day in class he realized, “If this is where God wants me to rest my head for the rest of my life, this is where I’m going to serve Jesus Christ for the rest of my life,” and he was resigned to spend the rest of his life in prison.

Chestnut, Watkins and Stewart had virtually no experience with the law on Nov. 18, 1983, and teachers who saw them in Harlem Park Junior High School that day described them “as silly and immature, not threatening,” said Lauren Lipscomb, the head of the Conviction Integrity Unit. The teens never denied being in the school and said they goofed around at their friends’ houses long into the afternoon after being kicked out of the school about 12:45 p.m.

Duckett was headed to lunch with two friends when someone came up and demanded his Georgetown Starter jacket at 1:15 p.m. His two friends ran. As Duckett was struggling to get the jacket off, he was shot. He ran to the cafeteria and collapsed, conscious but unable to speak, and died two hours later.

“Two individuals called in saying Michael Willis was the shooter,” Lipscomb said. One witness picked Willis out of a photo array as the shooter. Another student saw Willis run from the school and throw away a handgun. The reports on all of this were not given to the defense by the prosecutor Shoup. “You cannot make this up,” Lipscomb said. “It is just outrageous.”

Detective Kincaid showed photos of Chestnut, Watkins and Stewart to three witnesses. Twice, all three witnesses did not identify any of them, the newly released reports show. But the witnesses were repeatedly pulled from school over subsequent months and coached to identify the three teens, Lipscomb said. Kincaid flatly denied this. At trial, with the defense unaware they had not identified the teens initially, their testimony was devastating. All three have now recanted their testimony, Lipscomb said.

“The detective didn’t care,” Watkins said. “When we told the truth, he didn’t care.”

When police arrived at each of the teen’s houses at 1 a.m. on Thanksgiving Day 1983, they had a search warrant for Chestnut and found a Georgetown Starter jacket in his closet. His mother had the receipt for the jacket and showed it to police, Chestnut said. No blood or physical evidence tied the coat to Duckett or the shooting. But Shoup told the jury the victim’s jacket was in the defendant’s closet, another powerful piece of evidence that prosecutors now say was false.

At sentencing, Stewart told the court: “You still didn’t get the person who did it. I’m saying we know we didn’t do it, and a lot of other people know we didn’t do it.”

The men became eligible for parole in recent years, but all three declined to accept responsibility for the slaying, and so even when parole commissioners recommended them for release, the Maryland governor refused.

“I can’t sit up there and tell somebody I killed somebody when I didn’t,” Watkins said.

Watkins expressed sorrow for Duckett’s family, for having to revisit their loss and for knowing that justice wasn’t done. Lipscomb said that she met with the family and that they were unsurprised by the exoneration. She said one of Duckett’s brothers had always felt Willis was the killer.

On Sunday, the three exonerees were still trying to process their visit from Mosby two days earlier, and the possibility that they would be released Monday. “I’m all over the place in my head,” Watkins said.

“I broke down crying,” Stewart said. “I cried like a baby.”

“I feel like all these years I’ve been saying the same thing,” Chestnut said. “Finally, somebody heard my cry. I give thanks to God and Marilyn Mosby. She’s been doing a lot of work for guys in my situation.”

On Monday, their final court appearance was over in less than half an hour. Lipscomb and the defense attorneys asked the judge to grant a writ of actual innocence, which he did, ordering a new trial. Lipscomb then listed all the evidence that was withheld from the men’s lawyers in 1984, to the judge’s apparent disbelief.

Lipscomb proceeded to dismiss all charges against all three men. “Happy Thanksgiving,” she added, and the audience cheered.

You may be interested

WAFU B U-17 Girls Cup: Ghana Edge Gallant Flamingos On Penalties In Final

Webby - December 22, 2024Despite a spirited performance Nigeria’s Flamingos lost on penalties to hosts Ghana on penalty shootout in the final of the…

Bournemouth Equal Burnley’s Old Trafford Feat After 3-0 Win Vs United

Webby - December 22, 2024Bournemouth’s 3-0 win against Manchester United on Sunday meant the Cherries equaled Burnley’s feat at Old Trafford.United went into the…

Vitolo Announces Retirement From Football

Webby - December 22, 2024Former Spain forward Vitolo has announced his retirement from football.The former Atletico Madrid, Las Palmas and Sevilla confirmed his retirement…

![American Pastor, David Wilson Seen Eating The Box Of Woman Who Isn’t His Wife [Video]](https://onlinenigeria.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/american-pastor-david-wilson-seen-eating-the-box-of-woman-who-isnt-his-wife-video-150x150.jpg)

Leave a Comment