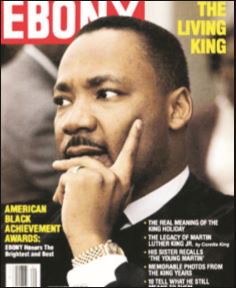

WITH the recent sale by public auction of its archives of more than four million black-and-white photographs, some of them prize-winning and some never published before, the monthly lifestyle magazine EBONY which defined and captured the black experience in America like no other for two generations has finally gone out of business.

Priced at $46 million, the archives were sold for $30 million. The proceeds will be used to offset part of the debts of the Johnson Publishing Company, owners of the magazine. The company filed for bankruptcy liquidation, some three years ago, unable to arrange financing or a sale.

Fears were rife that EBONY’s iconic pictures would fall into the hands of a private-equity firm that may choose to dispose of them as it pleases. In the event, they were purchased by a consortium of four leading private foundations, which will donate them to the National Museum of African American History and Culture at the Smithsonian Institution and the Getty Research Institute.

This arrangement guarantees the archives will be preserved for posterity and made accessible to the public

EBONY was launched in 1945, in Chicago, by John H. Johnson, a visionary entrepreneur concerned “to show the Negroes (as African Americans were then called) but also white people that Negroes also got married, held beauty contests, gave parties, ran successful businesses, and did all the other normal things of life.”

Johnson’s daughter, who succeeded him as publisher, said the mission was to make EBONY the “curator of the African-American experience, past, present, and future.” It fulfilled the first two parts of its mission admirably. But its future now lies behind it, sadly, after a run of 71 years.

Within a few years of its debut, EBONY became a habit. There was hardly any black home in the United States where you would not find a copy. It was read and passed along, to be read and passed along until every member of the household had savoured its contents. Those who could not read were rewarded with its white-and-black pictures that captured arrestingly all aspects of black culture, from the ghetto to the executive suite, and the Boardroom, and ultimately to the Presidency.

It was a lifestyle magazine with a difference. It depicted African American entertainers, athletes and movie actors and performing artistes all right. But it also showcased black scientists, lawyers, diplomats, legislators, community leaders, inventors, engineers, astronauts, corporate executives, commanding officers in the armed services and, generally, achievers in every sphere of American life.

Its tone was optimistic, upbeat. But you could never accuse EBONY of puffery, for the stories were substantive, well researched, and very well written. The photo-essay it published from time to time was a model of story conception and execution.

Its stablemate Jet, published in a much smaller format, debuted in 1951 as “the weekly Negro news magazine.” Together, EBONY and Jet captured the essence of black life in America like no other journals. Their challenge was to define or redefine for America black Americans, who were for the most part presented with mutilated images of themselves by the dominant media.

The field was not entirely bereft of black journals. There were, for example, the Chicago Defender, the Baltimore Afro-American and Amsterdam News based in Harlem, New York. These were important voices and vehicles in their communities, but their circulation and impact were modest.

At the launch of EBONY, many newspapers in the American South, did not publish pictures of blacks as a matter of policy. Large sections of the print media did not report the stirrings that culminated in the civil rights movement, the sit-ins and protests that challenged Jim Crow laws and caused them to be abolished. It was only in the late 1990s that a newspaper in Jackson, Miss, sought to atone for this denial by omission and published supplements chronicling important news stories of the civil rights it had not reported.

Television was just as complicit.

EBONY changed all that. Black people, many of them for the first time, could see black people like themselves as leading achievers and key public figures, in positions they did not know black people could hold and performing roles they never thought black people could play; they saw Africans in their colourful native attires on the world stage as kings and presidents and prime ministers and statesmen.

It fostered black pride. It promoted Black role models and fired black aspirations. Its yearly issue profiling the 100 Most Influential Blacks in America was a parade of excellent role models for aspiring African Americans. And if you wanted to reach the attentive black audience EBONY was the medium that gave you the best value for your advertisement budget.

The coming of the Internet opened the era of free content. Television generally, and cable television in particular, offered round-the-clock programming that gravely undermined newspaper and magazine readership. Advertisers shifted to digital platforms and television even as newspaper production costs soared, forcing such venerable publications like TIME and NEWSWEEK to abandon the business model that had served them so profitably for decades.

EBONY’s fortunes contracted in this altered environment. Debts mounted. Operations became unsustainable. Unable to arrange financing or find a buyer, it filed for bankruptcy liquidation three years ago. The sale last month of its photography assets closed what will go down as one of the most eventful chapters in the history of American journalism and black culture.

Unfortunately, generations of Nigerians will probably remember EBONY in an entirely different context

Despite its iconic status in the African American experience, the magazine had no market presence in Nigeria or anywhere outside the United States. Many Nigerians were acquainted with it only by its reputation. Some had read pass-along copies at infrequent intervals, courtesy of Nigerians living in or returning from the United States. You certainly could not pick up a copy at the newsstand as you could TIME and Newsweek.

Still, in 1990, EBONY magazine figured in Nigerian politics the way few foreign journals had done before or since. In the process, it bequeathed the term Ebonygate to the nation’s vocabulary of sleaze.

Military president Ibrahim Babangida’s benighted Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) had sapped the economy, turning basic needs into luxuries and eviscerating the middle class. Hunger stalked the countryside, and many Nigerians were reduced to rummaging through dustbins for food scraps.

Anti-SAP demonstrations, which turned violent in many cities, broke out across the country, fuelled by rumours that Babangida had stashed away some $3 billion from the national treasury in foreign banks, and that he and his wife owned, among other properties, a diamond watch factory in France.

The organizers cited EBONY magazine as their source.

Conspicuous among the teeming protesters in Lagos was the respected educator and founder of Mayflower School, Ikenne, Dr Tai Solarin, in his trademark floppy hat, khaki shirt and shorts. In an interview he had made some reference to Babangida’s rumoured offshore wealth – a key grievance of the demonstrators.

The claim that the story came out of EBONY was implausible through and through. It was not EBONY’s fare. But no matter.

State security officials seized Solarin and subjected him to a brutal inquisition on live national television, conducted by Col. Kunle Togun, who had been living under a cloud of suspicion of complicity in the 1985 parcel-bomb murder of the crusading journalist, Dele Giwa

What was Solarin’s source? Did he verify it? As an educator and an influential citizen, was he unaware that he had an obligation to verify the information so as not to lend his authority to subversive rumours?

Official desperation did not end there. The authorities dispatched a team to Chicago to urge EBONY publisher Johnson to state categorically, for the public record, that at no time had the magazine carried the story attributed to it. Johnson refused the strange demand.

And to this day in Nigeria, Ebonygate carries the resonance of rumour, gossip, or falsehood, a slur on the reputation of the foremost journal of the African American experience that was.

You may be interested

NPFL: Defeat To Kwara United Painful — Nasarawa United Boss Yusuf

Webby - March 27, 2025Nasarawa United head coach Salisu Yusuf has reacted to his team’s 1-0 loss to Kwara United, reports Completesports.com. Emeka Onyema…

Cote d’Ivoire Withdraw As Host Of U-20 AFCON

Webby - March 27, 2025Cote d’Ivoire announced late Tuesday its withdrawal from hosting the 2025 U-20 Africa Cup of Nations just weeks before the…

2026 WCQ: Osimhen’s Goal Not Enough As Zimbabwe Hold Super Eagles In Uyo

Webby - March 25, 2025The Super Eagles of Nigeria were held to a 1-1 draw by Zimbabwe in their 2026 FIFA World Cup qualifying…

![American Pastor, David Wilson Seen Eating The Box Of Woman Who Isn’t His Wife [Video]](https://onlinenigeria.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/american-pastor-david-wilson-seen-eating-the-box-of-woman-who-isnt-his-wife-video-150x150.jpg)