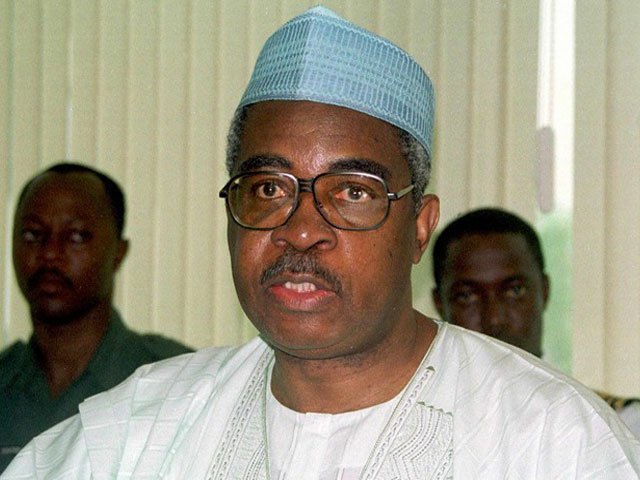

<!–  Top-B, left, Cahill, Grace Taiga, Supo Shasore. Middle, late Quinn who started the scam, Kuchazi of P&ID Nigeria and Mohammed Adoke, ex-Justice Minister –>

Top-B, left, Cahill, Grace Taiga, Supo Shasore. Middle, late Quinn who started the scam, Kuchazi of P&ID Nigeria and Mohammed Adoke, ex-Justice Minister –>

Top-B, left, Cahill, Grace Taiga, Supo Shasore. Middle, Quinn who started the scam, Kuchazi of P&ID Nigeria and Mohammed Adoke, ex-Justice Minister

By Bayo Onanuga

Sir Ross Cranston of the UK High Court of Justice Queen’s Bench Division Commercial Court, today allowed the Nigerian government to appeal the $10 billion awarded in arbitration to Process and Industrial Developments Limited(P&ID), for alleged breach of contract.

The ruling was given after Nigeria proved a prima facie case of fraud, around the contract about a so-called supply of wet gas to P&ID in Calabar.

In a nutshell, Nigeria, through the NNPC was said to have signed the contract with P& ID in 2009, during the Yar’Adua-Jonathan administration, with some public officials compromised with gifts of dollars and in some cases millions of Naira.

The contract was not meant to be implemented, but was meant as a vehicle to commit grand larceny against Nigeria, through some arbitration arising from a pre-arranged failed contract.

Rilwanu Lukman: he signed the dubious contract

But from the case filed in court by Nigeria, P&ID did not even pay a kobo, for the allocated land in Calabar to fulfil its own side of the contract, it did not erect a single block, but turned round to accuse Nigeria of failing to fulfil the terms of the contract.

It also came out that the Power Point presentation made by P&ID to bamboozle Nigerian officials to agree the contract, was for another project in Badagry funded by Tita-Kuru, a company owned by General Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma.

All P&ID expenses in dollars and Naira were channelled to bribing Nigerian officials to get former oil minister Rilwan Lukman to sign the contract papers.

Of course, the contract failed and P&ID proceeded to arbitration in London.

Abubakar Malami: working to overturn the arbitration award

This opened another chapter in the ignoble role of some Nigerians. According to the judgment read today, some Nigerian lawyers, who were supposed to represent Nigeria’s interest, half-heartedly defended Nigeria’s interest and allowed P&ID to run away with billions of dollars in arbitration award.

In a final ruling on 31 January 2017, the arbitration tribunal in London, ordered Nigeria to pay P&ID damages of US$6.6 billion, as well as pre- and post- judgment interest at 7 percent. The current outstanding amount is some US$10 billion.

General Theophilus Danjuma: his company had paid $40m to P&ID for the documents used to attempt a swindle on Nigeria

Luckily for Nigeria, the court admitted today that Nigeria has proven a prima-facie case of fraud around the project, from the award, and even to the arbitration level.

The court, in so doing, allowed Nigeria to challenge the arbitration award, even though, it is making the appeal out of time.

Every Nigerian needs to read the judgment reproduced below and will come out of it with tears for our country:

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION COMMERCIAL COURT

Case No: CL-2019-000752

IN AN ARBITRATION CLAIM

AND IN THE MATTER OF APPLICATIONS UNDER S.67 AND S.68 OF THE ARBITRATION ACT 1996

Before :

SIR ROSS CRANSTON sitting as a Judge of the High Court

———————

Between :

THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA

– and –

PROCESS & INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENTS LIMITED

——————— ———————

Claimant Defendant

Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL

Date: 04/09/2020

MARK HOWARD QC, PHILIP RICHES QC and TOM PASCOE (instructed by MISHCON DE REYA LLP) for the Claimant

IAN MILL QC and SIDDHARTH DHAR (instructed by KOBRE & KIM (UK) LLP) for the Defendant

Hearing dates: 13 and 14 JULY 2020 ———————

Approved Judgment

SIR ROSS CRANSTON sitting as a Judge of the High Court:

Introduction

1. These are applications by the Federal Republic of Nigeria (“Nigeria”) for an extension of time to bring challenges under sections 67 and 68(2)(g) of the Arbitration Act 1996 (“the 1996 Act” or “the Act”). There is a related application for relief from sanctions to adduce new evidence in response to an enforcement application. The hearing before me was by order of Butcher J in The Federal Republic of Nigeria v Process & Industrial Developments Limited [2020] EWHC 129 (Comm). It occurred over two days but, as I explain shortly, there were later written submissions about what was said to be new evidence.

2. These challenges and the enforcement application concern arbitral awards by a London Tribunal relating to a gas processing contract (“the GSPA”) between Nigeria and Process & Industrial Developments Limited (“P&ID”) dated 11 January 2010. The Tribunal’s Final Award of 31 January 2017 ordered Nigeria to pay P&ID damages of US$6.6 billion, as well as pre- and post- judgment interest at 7 percent. The current outstanding amount is some US$10 billion.

3. Nigeria’s case for an extension of time is that the GSPA, the arbitration clause in the GSPA and the awards were procured as the result of a massive fraud perpetrated by P&ID, and that to deny them the opportunity to challenge the Final Award would involve the English court being used as an unwitting vehicle of the fraud. P&ID’s case is that the awards date back some three to five and a half years and it would be unprecedented to grant the extensions. Speed and finality are essential features of London arbitration and the case that there has been any fraud (which is denied) is at best weak.

4. The parties have produced a large volume of documents, some thirty-four bundles with hundreds of pages of evidence and thousands of pages of exhibits. It is not my function at this preliminary stage to decide whether a fraud took place. As Butcher J pointed out in ordering the hearing, it would tend to defeat the purposes of the 1996 Act for there to be a substantial investigation of the merits at this stage: at [30]. However, it has been necessary to consider a considerable amount of the material to decide firstly, whether, as Nigeria contended, there is a prima facie case of fraud and how strong that case is, and secondly, the steps Nigeria took to investigate the alleged fraud from late 2015. Both matters are relevant to the issues of whether Nigeria’s claim is barred altogether and whether time should be extended in its favour and relief from sanctions granted.

5. Following the hearing, P&ID submitted a Supplementary Note to comment on new evidence which it said had only now come to its attention, in particular a letter dated 5 June 2020 from Nigeria’s Attorney General and Minister of Justice, Mr Abubakar Malami SAN, to President Buhari. P&ID contended that the letter strongly supported the case it advanced at the hearing. On 21 August Nigeria sent a Note in response, together with the eighth witness statement in the proceedings from Mr Malami. The material is considered later in the judgment.

Background

P&ID and Project Alpha

6. The defendant, P&ID, was incorporated in the British Virgin Islands (“BVI”) on 30 May 2006 by Michael Quinn and Brendan Cahill, both Irish citizens. In July 2006 an associated company, Projects & Industrial Developments (Nigeria) Ltd (“P&ID Nigeria”), was established. P&ID had no assets, only a handful of employees, and was without a website or other presence.

7. Messrs Quinn and Cahill had a number of other companies relevant to this case, including an Irish company, Industrial Consultants International Ltd (“ICIL”). There was also Lurgi Consult Ltd (“Lurgi”), a Cypriot consulting company in the oil and gas industry. Its Nigerian counterpart had as its directors Adam Quinn, Mr Quinn’s son, and James Nolan. Other associated companies appear in the course of the judgment.

The narrative conveniently begins on 27 June 2006, when P&ID signed an engineering service agreement with General T. Y. Danjuma (retired), a prominent Nigerian businessman, for the undertaking of what was called Project Alpha. That was followed by a further engineering service agreement of 6 September 2006 with General Danjuma’s company, Tita-Kuru Petrochemicals Ltd (“Tita-Kuru”). Project Alpha concerned the design of a polypropylene plant in Badagry, south-west Nigeria.

8. The narrative conveniently begins on 27 June 2006, when P&ID signed an engineering service agreement with General T. Y. Danjuma (retired), a prominent Nigerian businessman, for the undertaking of what was called Project Alpha. That was followed by a further engineering service agreement of 6 September 2006 with General Danjuma’s company, Tita-Kuru Petrochemicals Ltd (“Tita-Kuru”). Project Alpha concerned the design of a polypropylene plant in Badagry, south-west Nigeria.

9. In a letter to the Economic & Financial Crimes Commission (“EFCC”) dated 20 September 2019, Tita-Kuru states that one aspect of the arrangements with P&ID was that it would organise a gas off-take agreement from the Folawiyo gas field at Badagry, but that it later informed Tita-Kuru that it was unsuccessful in doing this. The letter continues that Mr Quinn of P&ID suggested that the engineering work undertaken could be used for a similar gas stripping plant at Calabar, capital of Cross River State in south-east Nigeria. The letter continues:

“3.1.6…We are therefore persuaded the studies, technology licensing fees and engineering designs that formed the basis of P&ID’s presentation to the Federal Ministry of Petroleum Resources were, in fact, ours…

3.2.2…[A]s per the matters in paragraph 3.1.6 hereof, we had paid the sum of $40m (Forty Million USD) to P&ID for the development of the Engineering work, Design and Off-take Consultancy Services which P&ID later used in their presentation to FMPR [Federal Ministry of Petroleum Resources] to secure the now disputed [GSPA].”

10. The letter also explains that there had been a falling out between Mr Quinn and General Danjuma but that later a memorandum of understanding was signed.

Steps leading to the GSPA

11. The reference in the Tita-Kuru letter to P&ID’s presentation to the Federal Ministry of Petroleum Resources (“MPR” or the “Ministry”) is to one of the steps in the negotiation of the GSPA. In October 2008 Mr Quinn made a power-point presentation at the Ministry. Slides 5 and 6 were computer aided design drawings, entitled “Propylene & Butane for Export, Phase 1” and “Propylene & Butane for Export, Phase 2”. They were both marked in boxes in the right side, lower corner, “Project Alpha”.

12. Another step was that P&ID had written to Nigeria’s President Yar’Adua with a formal proposal on 7 August 2008. (Nigeria does not admit that this letter was sent.) Amongst other points the letter stated that:

“we are willing to fund, from our own resources, the entire US$700,000,000 for the gas processing facilities on land and we are also willing, if necessary, to participate in all or part of the financing of the gas gathering offshore portion of the project…”

13. On 18 December 2008 Dr Rilwanu Lukman was appointed as Nigeria’s Minister of Petroleum Resources.

14. The following year there was correspondence and meetings between P&ID and members of the technical committee of the Ministry, among whose members were Dr M M Ibrahim (special senior technical assistant and head of policy at the government’s Oil & Gas Sector Reform Implementation Committee) and Mr Taofiq Tijani.

15. In June 2009 Mr Quinn wrote to the office of the Minister of Petroleum Resources, for the attention of Dr Ibrahim, enclosing P&ID’s letter to the Ministry in mid-March “detailing our expenditure of more than 40 million US dollars to date on the project”.

16. There was a Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”) signed on 22 July 2009 between the Ministry and P&ID Nigeria regarding the GSPA project.

17. On 1 December 2009 Dr Ibrahim sent a letter to P&ID indicating that Dr Lukman had “directed all stakeholders [to] fast track their processes”.

18. Just over a fortnight later, on 18 December 2009, Ms Grace Eyanena Taiga, legal director of the Ministry, sent a note to Dr Lukman advising him to sign the GSPA with P&ID. She wrote: “Subject to your comments to the contrary, I advise that HMPR [the Minister] signs these Draft Agreements to ensure a leap forward for Short Term Gas operations in the country as directed by Mr President.”

19. In his fourth statement for the court the Attorney General of Nigeria, Mr Malami, states that the GSPA did not obtain the requisite authorisation of the Bureau of Public Procurement or consent of either the Federal Executive Council or the Infrastructure Concession Regulatory Commission. Nor was it registered with the National Office for Technology Acquisition and Promotion. In his seventh statement, the Attorney General states that the individual at the Ministry responsible for compliance with these procedures was Ms Taiga.

The GSPA and immediate aftermath.

Clause 20 of the GSPA provided that, in the case of disputes, the parties could refer them to arbitration under the rules of the Nigerian Arbitration and Conciliation Act 2004. The venue of the arbitration was stated as London or otherwise as agreed by the parties. In his fourth statement the Attorney General, Mr Malami, states that the form of the arbitration agreement did not match the model reflected in a government circular in force at the time providing for arbitrations with their seat in Nigeria.

20. The GSPA was entered into between Nigeria and P&ID on 11 January 2010. It was signed by Dr Lukman on behalf of Nigeria. His signature was witnessed by Ms Taiga. Mr Quinn signed the agreement for P&ID, and his signature was witnessed by Mr Alhaji Mohammed Kuchazi, an associate of Mr Quinn.

21. Under the contract Nigeria was to supply natural gas (“wet gas”) at no cost to P&ID’s facility. For its part P&ID was to construct and operate the facility. It would process the gas to remove natural gas liquids – which P&ID was entitled to – and return lean gas to

Nigeria at no cost, which would be suitable for use in power generation and other purposes. The contract was to run 20 years from Nigeria’s first regular supply of natural gas to the facility.

22. Clause 20 of the GSPA provided that, in the case of disputes, the parties could refer them to arbitration under the rules of the Nigerian Arbitration and Conciliation Act 2004. The venue of the arbitration was stated as London or otherwise as agreed by the parties. In his fourth statement the Attorney General, Mr Malami, states that the form of the arbitration agreement did not match the model reflected in a government circular in force at the time providing for arbitrations with their seat in Nigeria.

23. A month later, on 11 February 2010, the Government of Cross River State wrote to P&ID, confirming approval for a grant of land, subject to payment of NGN21,015,138 (about £44,500).

24. On 14 May 2010 Mr Quinn wrote as chairman of P&ID to the incoming group managing director of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (“NNPC”), Nigeria’s state oil corporation. Mr Quinn requested assistance with the negotiations with Addax Petroleum, who were to provide the flared wet gas for the project. The letter stated that all necessary project finances were in place, 90 percent of the engineering designs were complete, a 50 hectare site had been allocated to P&ID by the Cross River State government, and Addax had confirmed its readiness to the Ministry to supply wet gas for the project.

25. Dr Lukman had ceased to be Minister for Petroleum Resources in March 2010. He was replaced the following month by Mrs Alison-Madueke. At the same time Mr Mohammed Bello Adoke SAN was appointed as the Nigerian Attorney General and Minister of Justice. As regards officials, Dr Ibrahim had left the Ministry on 1 February 2010. It seems that Ms Taiga left her position at the Ministry at some point later that year. Mr Tijani retired from the Ministry in January 2011. From 2011 until 2013 Ibrahim Dikko was legal adviser to the Ministry.

26. Between 2010 and 2012 P&ID wrote a number of letters to the Ministry, the NNPC and the President seeking implementation of the GSPA. There was a ministerial stakeholders meeting including P&ID in August 2010 and meetings with other stakeholders.

Commencement of arbitration

27. The GSPA was not implemented. On 22 August 2012 P&ID sent a Notice of Arbitration to Nigeria to commence proceedings under the Nigerian Arbitration and Conciliation Act 2004. Arbitration took place in three stages in London and resulted in three awards relating to jurisdiction, liability and quantum. Except to make sense of matters relevant to the current proceedings there is no need to set out the details of the arbitration and associated proceedings, which are dealt with in Butcher J’s judgment in Process & Industrial Developments Limited v The Federal Republic of Nigeria [2019] EWHC 2241 (Comm); [2019] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 361, [7]-[34].

28. In broad outline, P&ID and Nigeria appointed arbitrators in September and November 2012 respectively. In its initial statement of case P&ID alleged that Nigeria did not deliver the wet gas as required under the GSPA and had repudiated the contract, a repudiation which it had accepted. It claimed some US$6 billion in lost profits. P&ID served its Statement of Case in late June 2013. Nigeria’s notice of preliminary objection in October 2013 disputed the tribunal’s jurisdiction on the grounds that: (1) the GSPA was void because the Ministry, as a government body, did not have legal capacity to enter into contracts; and (2) the contract breached section 54 of the Companies And Allied Matters Act 2004, which requires foreign companies to carry out any business through a local subsidiary.

29. Mr Olasupo Shasore SAN was appointed as counsel for Nigeria in the arbitration. Mr Shasore was a former Attorney General of Lagos State, author of a textbook on Nigerian arbitration and a past President of the Lagos Court of Arbitration. He worked at a law firm, Ajumogobia & Okeke. The senior partner of that firm has given evidence to the EFCC that Mr Shasore kept his involvement in the case hidden and ran it through a different firm, Twenty Marina Solicitors, which was used to provide secretarial services. In a statement to the EFCC dated 24 December 2019, Mr Shasore has said that he was paid a fee of US$2 million for the first two stages of the arbitration, including disbursements.

30. On 14 February 2014 P&ID served its submissions on preliminary issues, with a witness statement from Mr Quinn and an expert report from Justice Alfa Belgore.

Evidence of Mr Quinn

31. Mr Quinn’s 34-page witness statement was dated 10 February 2014, which he gave as chairman of the company. Mr Quinn died in February 2015, before the liability hearing, and never gave evidence in person. In the arbitration P&ID relied on the factual evidence contained in the statement.

Mr Olasupo Shasore SAN was appointed as counsel for Nigeria in the arbitration. Mr Shasore was a former Attorney General of Lagos State, author of a textbook on Nigerian arbitration and a past President of the Lagos Court of Arbitration. He worked at a law firm, Ajumogobia & Okeke. The senior partner of that firm has given evidence to the EFCC that Mr Shasore kept his involvement in the case hidden and ran it through a different firm, Twenty Marina Solicitors, which was used to provide secretarial services. In a statement to the EFCC dated 24 December 2019, Mr Shasore has said that he was paid a fee of US$2 million for the first two stages of the arbitration, including disbursements.

32. After some introductory paragraphs, Mr Quinn stated at paragraph [4] of his statement that the GSPA represented a substantial project involving anticipated profits of $5 to $6 billion for P&ID over a 20 year period. The paragraph continued: “It was the culmination of years of research by my team of engineers into the production of clean energy from natural gas.”

33. Mr Quinn then set out what he said was his experience in Nigerian infrastructure projects (paragraphs [10]-[16]), before turning to the incorporation in July 2006 of P&ID Nigeria – the operating company – and P&ID, the BVI-incorporated company which signed the GSPA. As to P&ID he said: “I believe that the Government regarded the involvement of a BVI entity as a contracting party, rather than the Nigerian entity, to be commercially beneficial, especially from the perspective of the sale of NGLs [natural gas liquids] on the international markets”: para [21].

34. After passages on natural gas and power generation, the power crisis in Nigeria, and the country’s gas master plan, Mr Quinn’s statement turned to the nature of the project, the construction of a gas stripping plant. Work started in earnest, Mr Quinn said, in 2006: para [41]. A little later he said: “47. During the course of the next two years, we made good progress and reached a very advanced stage of the preparatory engineering work necessary to implement such a project on the ground. I would estimate that the total costs sunk into the preparatory work during that period were in excess of US$40 million, including initial feasibility studies, the cost of licences for the technology required to operate the gas stripping plant and the polypropylene plant respectively, the production of detailed engineering drawings and our own internal project management costs.”

48. By way of example, extensive work was commissioned from various specialist engineering companies…The cost of the work from these 3 companies alone was about $29 million…

49. By the end of the first 2 years of our work on the Project, we had put together a completed engineering package … which comprised about 100 volumes of documentation, together with a 3-D model of the plant…”

35. Mr Quinn then summarised what he said were the discussions with the government leading to the signing of the GSPA. Under the heading “Implementation of the GSPA”, Mr Quinn referred to a number of steps which he said P&ID had taken. One was that a site for the onshore gas stripping plant “had been selected by P&ID and secured…[and] on 16 February 2010 approval was granted, by the Government of the Cross River State, to P&ID, of the allocation of Parcels 1 & 2 of Energy City (Industrial) at Adiabo…”: para [109]. Mr Quinn added:

“110. On 14 May 2010, I wrote to NNPC [Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation] on the progress made by P&ID. I pointed out that all of the project finance was in place, 90 percent of the engineering designs had been completed, a 50 hectare site had been allocated to P&ID by the Cross River State Government…”

36. Mr Quinn’s statement then contained an account of what he said was the Nigerian government’s repudiation of the GSPA.

37. To his statement Mr Quinn exhibited the power-point presentation given at the Ministry in October 2008.

Jurisdiction Award and attempts at settlement

38. In its Partial Final Award of 3 July 2014, the Tribunal determined that it had jurisdiction and that the GSPA was valid and binding between the parties (the “Jurisdiction Award”). The Tribunal noted that in May 2014, Twenty Marina Solicitors had emailed the Tribunal stating that it would not be able to lodge Nigeria’s skeleton argument by the deadline or attend the jurisdiction hearing due to a difficulty in obtaining instructions. There was no request for an adjournment of the hearing, and the Tribunal dispensed with an oral hearing for the purposes of the award.

39. P&ID served its statement of case on liability on 28 June 2014. On 21 July 2014 the Tribunal ordered that Nigeria serve its statement of defence by 19 September 2014 (Procedural Order No.5). Nigeria did not comply.

40. There were then attempts at a settlement. On 17 July 2014 Mr Shasore had written to Nigeria’s Attorney General, Mr Adoke, that “there appears to be a lack of exonerating facts or any documentary evidence with which to defend the claim” and urged a “possible settlement”. On 11 August 2014 Mr Adoke then wrote to President Goodluck Jonathan expressing his agreement with Mr Shasore’s advice of mid-July that there were no “exonerating facts” and therefore “no legal grounds to defend the claim”.

41. Separately the NNPC wrote to the Minister for Petroleum Resources, Mrs Alison- Madueke, on 1 September 2014, agreeing with the Attorney General and outside counsel that the Ministry had “a bad case”. To that end it recommended that settlement be explored but that Nigeria should, nonetheless, file a defence. On 11 November 2014 the Attorney General wrote to Mrs Alison-Madueke, including the advice from Mr Shasore, urging her to pursue settlement discussions.

42. On 11 November 2014 Ms Folakemi Adelore, legal adviser to the Ministry from 2013 to 2017, sent a memorandum to the permanent secretary of the Ministry recommending a settlement with P&ID.

43. On 18 November 2014, US$100,000 of cash was deposited into Ms Adelore’s account in ten US$10,000 tranches. As explained later in the judgment, Mr Shasore and Ms Adelore accept that Mr Shasore was the source of the payment. There was an equivalent payment of US$100,000 to Mr Ikechukwu Oguine, who was the coordinator, legal services at the NNPC. Both Mr Shasore and Mr Oguine accept that Mr Shasore made the payment.

44. In December 2014 Mr Shasore, Ms Adelore and Mr Oguine travelled to London for settlement negotiations with P&ID.

45. On 30 December 2014 Ms Adelore wrote a memorandum to the Ministry’s permanent secretary. She stated that there was no doubt the Ministry was in breach of the GSPA; the negotiating team was apprehensive that the Tribunal might award P&ID’s claim of US$5.9 billion; and Nigeria should offer a lower amount which P&ID might accept.

The Liability Award

46. The Tribunal made Procedural Order No.6 on 16 February 2015, noting that Nigeria had missed an agreed, extended deadline of 3 October 2014 for filing its defence for the liability hearing, and ordering it to do so by 27 February. Nigeria’s statement of defence was filed and served by Mr Shasore on 27 February 2015.

47. On 17 March 2015 Mr Adoke, the Attorney General, forwarded a letter from Mr Shasore to the Minister for Petroleum Resources, Mrs Alison-Madueke, stating that “notwithstanding our line of defence, the Federal Government is still liable for failure to supply the requisite gas”. On 16 April 2015 Mr Shasore wrote to Mr Adoke, stating that the Ministry’s defence was in “grave need of evidence, documents and witnesses”, and asking for an “urgent response” on a proposal to settle the claim.

48. In response to Procedural Order No.8 directing Nigeria to serve its evidence and supporting documents by 1 May 2015, Nigeria served the witness statement of Mr Oguine, legal coordinator at the NNPC. The statement explained why Nigeria was unable to supply gas to P&ID and argued that its only role was as a “facilitator” between P&ID and the oil companies. There were no exhibits to the statement.

49. The Tribunal held a case management hearing by telephone on 6 May 2015. Neither side applied for cross-examination of witnesses. Following the case management hearing, the Tribunal made Procedural Order No.9 by consent. It required Nigeria to serve, within 48 hours, “a statement of any primary facts alleged in the evidence of Mr Michael Quinn which are challenged and of any other facts alleged to be relevant to the question of liability”. The Tribunal set down a hearing for 1 June, with 2 June in reserve.

50. On 12 May 2015 Mr Shasore served Nigeria’s statement of disputed facts. In substance they occupied less than a page and were six in number: P&ID’s knowledge that the Nigerian government had commenced building a pipeline; whether P&ID initially regarded Lagos as an attractive area for the project; whether the purpose of the GSPA was for P&ID to take wet gas free of charge from Nigeria; whether the government had access to “unlimited” supplies of natural gas in the Calabar area; whether Phase 1 of the contract was planned to take two years to implement after the grant of government approvals; and whether Nigeria was obliged to deliver wet gas free of charge to the site of the plant.

51. P&ID served its written arguments for the hearing on liability on 25 May 2015. On 28 May 2015 Nigeria did likewise, contending inter alia that the Ministry lacked capacity to enter the GSPA, that P&ID failed to fulfil its obligations under the GSPA, that construction of the gas processing facilities at Calabar was a precondition to Nigeria supplying wet gas, that the GSPA was for the supply of ascertained wet gas, misrepresentation by P&ID, fundamental change in circumstances, illegality, and that the GSPA was contrary to public policy and international law.

52. The liability hearing began at 10am on 1 June 2015 and ended early in the afternoon the same day. In the course of submissions on the first issue of the Ministry’s capacity to enter the GSPA, Mr Shasore stated that he hoped to cross-examine Mr Quinn on the matter. The chairman responded that there had been no application to cross-examine Mr Quinn. He added that P&ID had stated that it did not need to rely on the disputed facts Nigeria had raised on 12 May 2015, so that there was no scope for cross- examination.

53. Mr Shasore replied that that was not his understanding, and he applied to cross-examine Mr Quinn, at which point P&ID’s advocate informed the Tribunal that Mr Quinn had died earlier in the year. The Tribunal made a formal ruling: there was no application to cross-examine Mr Quinn, and under Procedural Order No. 9 Nigeria had to serve a statement of any primary facts in Mr Quinn’s affidavit which it challenged, and any other facts alleged to be relevant. Nigeria had done this, but P&ID took the view that none of the challenged facts were relevant to its claim and were content that those facts should not be accepted. The hearing continued.

54. In reply submissions following the hearing, Mr Shasore returned to his inability to cross-examine and asserted that his statement of disputed facts essentially challenged all the facts in Mr Quinn’s statement.

55. The Tribunal issued its Partial Final Award concerning liability on 17 July 2015, finding that Nigeria had repudiated the GSPA and that P&ID was entitled to damages (“the Liability Award”). As to the evidence, the Tribunal said at paragraph [35] that “although Mr Ikechukwu Oguine made what was called a witness statement, he gave no relevant evidence”; his statement consisted of references to documents on the record and submissions in similar terms to those made by Mr Shasore. The Tribunal used Mr Quinn’s evidence, where it had not been contested by Nigeria, as the factual basis of events preceding and subsequent to the GSPA. The Tribunal dismissed Mr Shasore’s defences to the claim.

President Buhari elected and the Quantum/Final Award

56. Having won the elections, President Muhammadu Buhari was sworn in on 29 May 2015. Professor Yemi Osinbajo became the vice-president. On 11 November 2015, Mr Malami was appointed as Attorney General and Minister of Justice. He continues in that role to the present day. In his sixth statement for this court he recalls that after his appointment he studied the arbitration case file and noticed some lapses in how the matter had been handled.

57. Meanwhile, on 27 October 2015, the Tribunal had made Procedural Order No.10, noting that Mr Shasore had informed the Tribunal that he was without instructions. The order required P&ID to serve its evidence on quantum and for Nigeria to serve reply evidence.

58. On 23 December 2015 Nigeria applied to this court for orders to make an out of time application to set aside the Liability Award on grounds of internal inconsistency in the Tribunal’s reasoning, the Tribunal’s failure to deal properly with the authority argument, and the Tribunal’s failure to give reasons that Nigeria’s breach was repudiatory. On 10 February 2016 Phillips J considered the application on the papers (as is customary) and rejected it: the application was more than four months after the expiry of the 28 day time limit, and for reasons he explained Nigeria had not shown compelling reasons for an extension. In refusing to extend time, Phillips J also took into account that the grounds had no merit, for reasons he explained.

59. Nigeria then filed an originating motion in the Nigerian Federal High Court. Dated 24 February 2016, it sought an order: (i) extending time to set aside the Liability Award; and (ii) setting aside and/or remitting for further consideration all or part of the Liability Award. On 5 April 2016 Nigeria also sought an order restraining the parties from participating in the arbitration, pending the court’s determination of the 24 February 2016 application. That was granted on 20 April 2016.

60. In response to the position where Nigeria had made an application to the Nigerian court, the Tribunal made Procedural Order No. 12 on 26 April 2016, setting out its reasons for finding that the seat of the arbitration was England, not Nigeria. Nigeria challenged the Order in the Federal High Court on 9 May 2016, but that application was struck out for want of prosecution later in the year.

61. On 24 May 2016 the Nigerian court made an order: (i) extending time for Nigeria to apply to set aside the Liability Award; and (ii) setting aside and/or remitting for consideration all or part of the Liability Award.

62. The Tribunal held a two-day hearing on quantum in late August 2016. Nigeria participated, while maintaining its position as regards the Liability Award.

63. By this time Mr Shasore had been replaced as Nigeria’s counsel by Chief Bolaji Ayorinde SAN. In a letter to the Vice President on 29 March 2017 the Attorney General, Mr Malami, stated that Mr Shasore had failed to cooperate properly in handing over material when his (the Attorney’s) office assumed the conduct of the case from the Ministry in mid-2016.

64. For the purposes of the quantum hearing both sides commissioned expert reports. P&ID had an expert report prepared by Berkeley Research Group LLC (“BRG”), dated 19 August 2016. Amongst other things it concluded, from reviewing P&ID’s CAD (computer aided design) model and its proposal to the government, that it was well advanced in its preparation to build the facility.

65. The Tribunal issued its final award on quantum on 31 January 2017 (the “Final Award”). In part E, “Findings on liability”, beginning at paragraph [29] it recalled its findings in the Liability Award. The evidence of P&ID, it said, consisted of a statement of Mr Quinn, parts of which it quoted, including his paragraph [110], set out earlier in the judgment. It then recalled Procedural Order No. 9, and that Nigeria had served a statement of the facts it challenged, but which P&ID had elected not to rely on.

66. Then in part G, “Measure of Damages” the Tribunal stated at paragraph [50] that the evidence showed a high degree of likelihood that if the government had been willing to perform, “P&ID was fully prepared to acquire the land and start constructing the plant”, quoting again from Mr Quinn’s statement. At paragraph [51] the Tribunal recalled Procedural Order No. 9, that Nigeria had not disputed any of the matters the Tribunal had mentioned and concluded: “P&ID thus showed every sign of being willing, indeed anxious, to implement the project and there is no dispute over its ability to have done so.”

67. By a majority the Tribunal found that, had Nigeria not repudiated its obligations under the GSPA, P&ID would have performed its obligations and had suffered loss. That was measured by the income it would have achieved in the 20 years of the contract from the sale of the NGLs which would have been extracted from the wet gas, less capital expenditure (“capex”) of some $500 million and $50m operating expense (“opex”) per annum. It awarded P&ID lost profits of US$ 6.6 billion, together with pre- and post- award interest of 7 percent.

Response to the Final Award

68. On 2 March 2017 there was a meeting at the Attorney General’s office to consider all options available to Nigeria. The meeting included Mr Malami, the Attorney General, the Nigerian law firm representing Nigeria in the arbitration and representatives of the Ministry and the NNPC.

69. Following that meeting, on 13 March 2017 Mr Malami wrote to Vice President Osinbajo, who was acting president at the time, exploring five “scenarios” and making recommendations on each. The first was to negotiate a reasonable settlement. The second was to undertake a “forensic and extensive examination of the original contract, Award and other Processes to discover loopholes to upset or vary the Award.” The merits were said to be that a loophole might be discovered, for example fraud, technical grounds or a conflict of interest of the arbitrators. The other options were to inquire whether there was the possibility of an appeal, an investigation by the EFCC and a challenge to the recognition and enforcement of the award.

70. Mr Malami wrote further to the Vice President on 17 March 2017, following a meeting on 13 March where the scenarios in the 13 March letter were “extensively deliberated”. Scenario 1 was now expressed as “the urgent need” (emphasis in original) to negotiate a settlement. The scenario about involving the EFCC was that it should be directed to undertake a discreet investigation of the matter, and also to ascertain the personalities and beneficiaries behind P&ID.

71. There was a further letter from Mr Malami to the Vice President dated 29 March 2017. On 6 April 2017 the Vice President approved in manuscript on the letter its proposal to pursue settlement negotiations.

72. There followed on 16 May 2017 (and afterwards) without prejudice settlement discussions with P&ID. After P&ID stated in September 2017 that it intended to enforce the Final Award, on 7 December 2017 the Vice President granted approval to negotiate further. However, settlement negotiations broke down.

73. The Attorney General, Mr Malami, together with the Minister of State for Petroleum Resources wrote to the Vice President on 23 May 2018 in light of US enforcement proceedings which P&ID had initiated, recommending the reopening of negotiations with P&ID while efforts were being made as regards the enforcement proceedings.

74. On 12 June 2018 the Vice President’s office reported that he had agreed with the recommendation and would take up the matter with the President. That same day, 12 June 2018, the Vice President wrote to the President recommending the reopening of negotiations with P&ID. The President approved this recommendation on 26 June 2018.

75. There was a meeting on 12 July 2018 in anticipation of settlement negotiations involving Nigeria’s international legal representatives, Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle LLP (“Curtis”), the Attorney General, Mr Malami, and Nigerian officials. A memorandum of the meeting records that Nigeria still preferred a reasonable settlement with P&ID. It added that the Nigerian team also alleged that there may be fraud involved in the circumstances surrounding the GSPA. However, the Curtis team “pointed out that in order to advance fraud…there is need to have concrete evidence of same”.

76. Negotiations with P&ID the following day, 13 July 2018, were unsuccessful.

Enforcement of the Final Award

77. Meanwhile, on 16 March 2018 P&ID applied to this court under section 66 of the 1996 Act for an order that it have leave to enforce the Final Award of 31 January 2017. Nigeria did not file an acknowledgement of service in time and applied for relief from sanctions. On 21 December 2018 Bryan J granted relief from sanctions: Process & Industrial Developments Limited v The Federal Republic of Nigeria [2018] EWHC 3714 (Comm). Meanwhile, on 28 March 2018, P&ID had commenced enforcement proceedings in the United States District and Bankruptcy court for the District of Columbia.

78. Nigeria raised a number of objections to the section 66 application, including that London was not the seat of the arbitration. In his judgment in Process & Industrial Developments Limited v The Federal Republic of Nigeria [2019] EWHC 2241 (Comm); [2019] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 361, handed down on 16 August 2019, Butcher J held that the Tribunal had correctly construed the arbitration clause in the GSPA that London was the seat of the arbitration, and its decision created an issue estoppel precluding Nigeria from raising the issue at the enforcement stage. He then went on to dispose of various grounds Nigeria had raised against enforcement, including that it would be against public policy. The application by P&ID to enforce the Final Award as a judgment or order of the court was consequently granted.

79. At a hearing on 26 September 2019 to consider consequential matters, Butcher J gave Nigeria permission to appeal: Process & Industrial Developments Limited v The Federal Republic of Nigeria [2019] EWHC 2541. In the course of his judgment he said:

“[15]…[T]here has been some mention before me of there being an investigation conducted by Nigeria into the award of the GSPA and related matters. There is a suggestion that there may have been some sort of fraud, conspiracy or tax evasion. Those were not grounds which were relied upon before me at the hearing in June as reasons why the Final Award should not be enforced. They are not relied upon now as reasons for the grant of permission to appeal nor as grounds of appeal. On the contrary, Mr Matovu’s skeleton argument states in terms that ‘The court is not asked to act on these investigations or convictions at the present hearing.’ Those allegations have accordingly played no part in my decision in relation to permission to appeal.”

80. Nigeria launched the current challenges under sections 67 and 68(2)(g) of the 1996 Act on 5 December 2019. As we have seen, on 24 January 2020 Butcher J ordered Nigeria’s applications for an extension of time and relief from sanctions to be heard as preliminary issues and not as part of a rolled up hearing with the substantive applications: The Federal Republic of Nigeria v Process & Industrial Developments Limited [2020] EWHC 129 (Comm). That is the present hearing.

81. On 29 January 2020 Flaux LJ, the supervising Lord Justice of the Commercial Court, stayed the appeal from Butcher J’s enforcement order pending the outcome of this hearing.

EFCC investigations

82. The EFCC is a statutory body under the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (Establishment) Act 2004, with power to conduct investigations into whether any person has committed an offence under the legislation constituting it or any other law relating to economic and financial matters.

2016 investigation

83. In February 2016 the Attorney General, Mr Malami, asked the EFCC to investigate P&ID.

84. This investigation was the result of a letter of 1 February 2016 from Stephenson Harwood to Ms Adelore, the legal advisor to the Ministry. Nigeria had engaged the firm to assist it. It had written recommending that sufficient resources be deployed to challenge the legal and expert evidence submitted by P&ID. Further, it said, a credible investigations company should be appointed to carry out investigations into the history, financial capability and track record of P&ID given its offshore structure, apparently small size and lack of significant track record. The letter commented that this may assist Nigeria at the quantum stage of the arbitration either directly or indirectly.

85. For the purposes of its inquiry, the EFCC requested that the legal directors of the Ministry (Ms Adelore) and the NNPC (Mr Oguine’s successor) be released for interviews as part of the investigation into what it described as a case of conspiracy, abuse of office and misuse of public funds. From late February 2016 until 2 March 2016 these officials were interviewed and provided the EFCC with documents relating to the GSPA and the arbitration. In a briefing note for the EFCC, Ms Adelore criticised Mr Shasore’s strategy in the arbitration. In April-May 2016 the EFCC conducted further meetings with the NNPC and reviewed the GSPA, the July 2009 MOU and other documents received from both the Ministry and the NNPC.

86. On 16 June 2016 the EFCC submitted an interim report. In the section headed “Findings”, the report canvassed the background to the GSPA. It noted that the process of awarding the GSPA

“was significantly hinged on the report of the technical committee of the [Ministry] [and] had the certification and recommendation of the legal unit of the Ministry and that the agreement was signed by the Legal Adviser, Grace Taiga, as a witness to the MOU and the [GSPA]”.

The report observed that the Tribunal appeared to have acted on the material before it, although there were “strands of information that the panel acted out of the scope of its work. Focus should be the underlying transaction, if anything.”

87. The interim report then set out short conclusions and recommendations. P&ID, it said, was not entirely blameless “as there are key gaps noticed in the transaction for which it may be necessary to go beyond their capacity.” It added: “It is definite that the award of the contract by the [MPR] was a function of the recommendation of the technical committee of the Ministry.” While the technical committee of the Ministry had experts, the report continued, “the findings of gaps in the reasons for default by parties might require a further investigation”. It recommended a “further detailed investigation of the circumstances surrounding the award of the contract and the key parties to the transaction”.

On 12 June 2018 the Vice President’s office (no doubt using his manuscript on the joint ministerial letter) replied formally to the Attorney General and Minister of State, stating his view that “the whole arrangement amounts to a fraud on the nation”, and that he had therefore additionally recommended to the President “the need to independently investigate all the relevant circumstances”.

EFCC investigation beginning June 2018

88. On 13 April 2018, the NNPC wrote to the Attorney General, Mr Malami, reminding him that at a meeting on 2 March 2017 it had identified deficiencies in the GSPA and suggesting among the options for resolving the P&ID matter that there be an independent forensic examination of the entire case file.

89. As referred to earlier, the Attorney General together and the Minister of State for Petroleum Resources had written to the Vice President on 23 May 2018 recommending further negotiations with P&ID. The Vice President had agreed, adding in manuscript on the letter that he was still of the opinion that the underlying transaction was “a fraud on the nation”, and that perhaps there might be “a need to independently review this view and investigate the entire affair more diligently”.

90. On 12 June 2018 the Vice President’s office (no doubt using his manuscript on the joint ministerial letter) replied formally to the Attorney General and Minister of State, stating his view that “the whole arrangement amounts to a fraud on the nation”, and that he had therefore additionally recommended to the President “the need to independently investigate all the relevant circumstances”.

91. That same day, 12 June 2018, the Vice President wrote to the President recommending that as well as reopening negotiations with P&ID he might also wish to direct the acting chairman of the EFCC “to independently investigate all relevant circumstances surrounding the transaction underlying the arbitral award with a view to determining whether or not there was a fraudulent intent in the conception of the agreement”.

92. The President issued a direction on 26 June 2018 that the Ministry and the Ministry of Justice was to provide all necessary information, documents and support to the EFCC to enable a thorough investigation of the circumstances surrounding the GSPA and subsequent events. In addition, he directed the Director-General of the National Intelligence Agency to investigate P&ID with a view to uncovering the identities of all the promoters, directors and shareholders of the firm. The President also ordered an urgent review into any lapses that had led to the current situation.

93. On 28 June 2018 the Attorney General, Mr Malami, wrote to the acting chairman of the EFCC, passing on the President’s instructions to conduct “a thorough investigation of the circumstances surrounding the [GSPA] and the subsequent events”. As well he sent the documents his department had as part of the inquiry.

In a letter of 4 September 2019 to the EFCC, the Director of Lands of Cross River State wrote that a letter of allocation was only issued to applicants on payment of all the land charges and fees within the 120 days specified. P&ID could not claim that the land had been allocated to it in 2010, since there was no proof of payment and no issuance of a Certificate of Occupancy.

94. In his sixth witness statement in these proceedings, Mr Malami states that the EFCC investigation began with research into open and closed sources, including the profiling of some thirty potentially relevant suspects. In August 2018 information requests were sent to various government agencies. In January 2019 the EFCC requested further information from the Ministry of Lands at Cross River State and the Federal Inland Revenue Service.

Events after Butcher J’s judgment of 16 August 2019 including P&ID’s conviction

95. Following Butcher J’s judgment of 16 August 2019, which meant that P&ID could enforce the Final Award, on 20 August 2019 Nigeria’s Solicitor General involved the Nigerian police in the investigation into P&ID. The Attorney General states in his sixth witness statement that this was because of the EFCC’s limited remit to financial and related matters.

96. On 28 August 2019 the Federal Inland Revenue Service informed the EFCC that P&ID had not opened a tax file. Early the following month, on 3 September 2019, the Special Control Unit against Money Laundering reported that P&ID Nigeria had failed to register its activities with it.

97. In a letter of 4 September 2019 to the EFCC, the Director of Lands of Cross River State wrote that a letter of allocation was only issued to applicants on payment of all the land charges and fees within the 120 days specified. P&ID could not claim that the land had been allocated to it in 2010, since there was no proof of payment and no issuance of a Certificate of Occupancy.

98. Criminal proceedings against P&ID, Ms Taiga, Mr Cahill and Mr Kuchazi were commenced on 17 September 2019. Two days later, on 19 September 2019, P&ID and P&ID Nigeria pleaded guilty before Ekwo J in the Federal High Court to ten and eleven counts respectively relating to conspiracy to defraud Nigeria, money laundering, tax evasion and trading without proper authorisations. The convictions were on evidence given by an officer of the EFCC.

EFCC: interview and statements

99. The EFCC began interviews in September 2019. Included among those interviewed was Ms Taiga, who had been the senior lawyer in the Ministry until 2011. She was detained between 3 September 2019 and 21 September 2019. She gave a statement on 11 September 2019. She has complained about her treatment when detained.

100. The EFCC interviewed Mr Tijani under caution on 4 September 2019. At the time of the GSPA he was a member of the Ministry’s technical committee. He told the EFCC that the committee’s role was to conduct due diligence on projects, including P&ID’s. He denied wrongdoing, receiving gifts and recalled that he had no objections to P&ID’s project and subsequently recommended it.

101. During a further interview on 15 November 2019 – once EFCC had accessed certain bank records – Mr Tijani accepted that he had received bribes from P&ID in return for overlooking shortcomings in its bid. His account is also contained in a witness statement for this court; it is summarised later in the judgment. In response to a letter from Mr Tijani in early December 2019, the Attorney-General entered a non- prosecution agreement with him on 8 January 2020.

102. In a statement to the EFCC on 13 September 2019 Mr Oguine, legal director at the NNPC at the time, said that Mr Shasore – counsel for Nigeria in the arbitration – offered him US$100,000 towards his (Mr Oguine’s) expenses. Mr Oguine initially declined but eventually took the money on the basis that it would be repaid as a loan. No part had yet been repaid. Mr Oguine also stated that he was charged with obtaining potential witnesses of fact for the liability hearing before the Tribunal. No witnesses could be found, so Mr Shasore prepared a witness statement which he reviewed and signed.

103. As explained earlier in the judgment, in a letter to the EFCC on 20 September 2019 General Danjuma’s company, Tita-Kuru, stated, in effect, that P&ID had stolen its plans for a gas stripping plant which it then used to obtain the GSPA.

104. Mr Shasore, who conducted the arbitration for Nigeria at the jurisdiction and liability stages, was interviewed on 24 December 2019. He told the EFCC that he made personal gifts of US$100,000 each to Ms Adelore (the senior lawyer at the Ministry) and Mr Oguine (legal director at the NNPC).

105. In an interview on 6 and 7 May 2020 Ms Adelore accepted that she received an unsolicited payment of US$100,000 in cash from Mr Shasore, which she had a colleague collect from Mr Shasore’s office. She has told the EFCC that she felt Mr Shasore was working against Nigeria’s interests in the arbitration.

In an interview on 6 and 7 May 2020 Ms Adelore accepted that she received an unsolicited payment of US$100,000 in cash from Mr Shasore, which she had a colleague collect from Mr Shasore’s office. She has told the EFCC that she felt Mr Shasore was working against Nigeria’s interests in the arbitration.

EFCC: bank records

106. During its inquiries EFCC obtained bank statements and Swift records of interbank payments in relation to various accounts. Among the information obtained from September 2019, and the date EFCC obtained it, is the following (described in greater detail later in the judgment under “Payments/bribes”).

107. Ms Taiga received two cash transactions of US$10,400 and US$6,500 into her Access Bank account (but not linked to P&ID) (information EFCC obtained on 27 September 2019). There were payments in 2017 into her Zenith Bank account from Eastwise and ICIL (information EFCC obtained on 2 October 2019). Her daughter received payments from ICIL, Ireland, in March 2019 (information EFCC obtained from Citibank NA, London, 2 March 2020).

108. Dr Lukman opened a US Dollar account at GT Bank on 16 January 2009, with an initial cash deposit of US$10,000. Dr Lukman then deposited a further US$10,000 of cash into another GT Bank account on 8 April 2009 (information EFCC obtained on 5 October 2019).

109. Mr Tijani received two payments from Lurgi totalling around £30,000 in April 2014 and April 2015 (information EFCC obtained early November 2019).

110. Dr Ibrahim, a member of the technical committee reviewing the GSPA, opened a US dollar account on 28 April 2008 under the name of his company, Equatorial Petroleum Coastal & Process Limited, with an initial cash deposit of US$10,000. There were further periodic cash deposits totalling US$69,300 until 2015. On 28 October and 1 December 2008 there were also two cash deposits totalling NGN 4,000,000 (approximately £8,500) into his personal account at First Bank.

111. In March this year Nigeria applied to the US District Court for the Southern District of New York under 28 USC [United States Code] § 1782(a) to obtain discovery of bank accounts at ten different banks. P&ID intervened in the course of the application. It stated that it did not object to the order although its submission to Judge Schofield was that the use of the information obtained should be limited to criminal prosecutions in Nigeria.

112. The US court made disclosure orders on 7 May 2020. As a result of the application Nigeria obtained information, including payments to Ms Taiga’s daughter in 2009 and 2012.

Role of acting chairman of EFCC, Mr Ibrahim Magu

113. After the hearing I received written submissions relating to the role of acting chairman of EFCC, Mr Ibrahim Magu. On 5 June 2020 the Attorney General, Mr Malami, had sent a letter to President Buhari headed “Flagrant abuse of public office and other infractions committed by Mr Ibrahim Magu, acting chairman of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission”. In the course of the letter the Attorney General stated that as regards the investigation of P&ID, although he had passed on the President’s direction in June 2018, the EFCC “did not accord this presidential directive with any serious attention until a year after around July/August when the scale had already tilted dangerously against Nigeria”. In view of the delay, the Attorney General continued, he had involved the police. That had prompted Mr Magu to prosecute charges against P&ID, but without recourse to the wider team.

114. Mr Magu was detained on 6 July 2020 and a panel is investigating matters. On 31 July 2020, after the hearing before me, a Nigerian news outlet, The Cable, published what purported to be a copy of the Attorney General’s letter of 5 June 2020 and the reply of Mr Magu. In Mr Magu’s reply he says that the EFCC investigation was conducted expeditiously in 2018-2019, and that a staggering and unprecedented volume of work was done in less than a year.

115. After The Cable report, on 4 August 2020, the Attorney General wrote again to the President under the same heading. He sought to clarify that his complaint was against Mr Magu and his lack of support within the EFCC for the P&ID investigation. The EFCC had begun the investigation, he said, but it had taken a lot of coercion from his office to have the investigation progress. Under Mr Magu, said the letter, the EFCC did not share information with the Attorney General’s office or the police.

116. In a further statement for the court Mr Malami states that he has never seen what is reported as Mr Magu’s letter and his understanding is that the President has never received it. He states that despite his criticisms of Mr Magu’s personal handling of the EFCC investigations into P&ID, the investigation itself made excellent progress.

Payments/alleged bribes

117. In his fourth witness statement in these proceedings the Attorney General, Mr Malami, acknowledges that fraud has been endemic in Nigeria, until the arrival of President Buhari in 2015 at the very highest levels, and especially in the oil and gas sector. He adds that the endemic corruption, which the present regime was taking great strides to eliminate, was in existence at the time the GSPA was entered into, when the dispute arose and during the early stages of the arbitration.

118. The alleged bribes which Nigeria relied on for the purposes of the hearing were collected in a schedule. In summary the date and amount of these payments, their source, and the date Nigeria uncovered them, are as follows:

Ms Taiga, senior legal adviser to the Ministry at time of GSPA

119. On 19 and 20 August 2010 Ms Taiga made two payments into her Access Bank account, in total US$10,400.

Ms Taiga says this cash may well have come from the sale of a car or property from her late mother’s estate. In her second statement, she says that it represented the proceeds of sale of a number of vehicles and a plot of land.

120. There was a further deposit of US$6,500 on 14 June 2013 in the Access account. Ms Taiga made a payment to her daughter the same day of US$6,500. In her first statement

Ms Taiga says that the US$6,500 may have been a loan from a family member intended for her daughter.

121. Ms Taiga received US$1,000 on 14 September 2015 from Eastwise Trading Ltd; US$10,000 on 18 December 2017 from ICIL; and US$10,000 on 27 June 2018, also from ICIL. Eastwise and ICIL are associated companies of P&ID.

122. There were payments of EUR 500 on each of 1 March and 25 March 2019 from ICIL. The EFCC uncovered these on 2 March 2020.

123. Mr Cahill says he has made further transfers to Ms Taiga since she was released from custody, but there is no information about how these payments were made and in what amount.

Ms Taiga’s daughter

124. As a result of its application in New York under 28 USC § 1782(a) in March this year, Nigeria discovered payments to Ms Taiga’s daughter of US$4,969.50 on 30 December 2009 and US$5,000 on 31 January 2012 respectively. Their source was companies associated with Messrs Quinn and Cahill, Marshpearl Ltd and Kristholm Ltd respectively.

Mr Tijani, member of the Ministry’s technical committee at time of GSPA

125. In addition to the US$50,000 cash which Mr Tijani says he was given as a gift in April 2009 – described shortly – there was a payment of some US$30,000 by SESFTF Progress Limited (a company controlled by Messrs Quinn and Cahill) to Conserve Oil Limited (“Conserve Oil”) (a company associated with Mr Tijani). In addition, Lurgi (a company associated with P&ID) paid Mr Tijani NGN 3,440,000 (approximately £15,310) on 3 April 2014. The same day Mr Tijani was paid NGN 4,350,000 by Conserve Oil. A year later, on 22 April 2015, he was paid NGN 4,000,000 (approximately £13,375) by Lurgi.

Ibrahim Dikko, Ms Taiga’s successor as legal adviser to the Ministry

126. Mr Quinn offered him US$2,000 in cash to attend the International Bar Conference in Dublin, which he accepted (although he does not appear to have attended).

Ms Adelore and Mr Oguine, legal directors at the Ministry and NNPC respectively

127. Already mentioned are the payments of US$100,000 to each of Ms Adelore and Mr Oguine by Mr Shasore on 18 November 2014 (Ms Adelore) and in 2014/2015 (Mr Oguine) respectively.

Other payments

128. Nigeria also relies on the payments into the bank accounts of Dr Lukman and Dr Ibrahim, referred to earlier. Nigeria states that their source is unknown at this point.

129. In addition to these specific payments, Nigeria also points to a spike in withdrawals from ICIL Nigeria’s bank account in Q2 of 2008 and Q1 of 2010 by James Nolan, a long-time business associate of Messrs Quinn and Cahill, and by ICIL’s accountant, Mr Anekperechi Nworgu. In total these amounted to US$770,000 and NGN 15,000,000 (approximately £122,000) and were mainly in cash.

Witness statements

130. There are some 34 witness statements before the court, including eight from the Attorney General, Mr Malami. At this point, I offer brief summaries of what I see as the key statements and those which require mention in fairness to their deponents.

Ms Taiga

131. As we have seen, Ms Taiga was legal adviser to the Ministry at time of GSPA. In her first statement she says that at no time did she provide illegitimate assistance to P&ID. She provided legal assistance to her Ministry and did not negotiate the commercial terms of contracts, and that included the GSPA. She witnessed Dr Lukman’s signature, but that was routine. She was not responsible for ensuring compliance with public procurement or other legislation. As far as she was aware other ministries and departments were aware of the GSPA. The GSPA appeared a perfectly legitimate contract.

132. After she retired in September 2010, she says, she remained in touch with Mr Quinn. The payments which Mr Cahill made to her between 2015 and 2019 were as a favour, and at her request, to meet medical expenses. As regards the payment of US$10,400 into her Access bank account on 19 and 20 August 2010, Ms Taiga says this cash may well have come from the sale of a car or property from her late mother’s estate. Ms Taiga says that the US$6,500 deposited on 14 June 2013 may have been a loan from a family member intended for her daughter, not from Messrs Quinn or Cahill or anyone associated with P&ID.

133. In her second statement, Ms Taiga clarifies what she had previously said about the deposit in her bank account on 19 and 20 August 2010 and explains that it represented the proceeds of sale of a number of vehicles and a plot of land. As to the payments to her daughter in December 2009 and January 2012 by companies associated with Messrs Quinn and Cahill, she says that they provided financial support for private medical treatment in London and had nothing to do with the GSPA.

Mr Tijani

134. Mr Tijani was a member of the Ministry’s technical committee until he left in January 2011 to become (until 2015) the Commissioner of Energy and Mineral Resources in Lagos State.

135. In his first statement to the court, Mr Tijani states that he was chairman of the technical committee to review P&ID’s proposal. He says that in early 2009 he attended an unusual meeting in the office of Dr Lukman, the Minister of Petroleum Resources at the time. Mr Quinn, and a colleague, Neil Hitchcock, were there. Dr Lukman directed him to recommend P&ID’s project. After the meeting Mr Hitchcock dropped a black bag into his car, describing it as a “gift” and that they normally took care of their friends. It contained US$50,000 in cash.

136. Mr Tijani explains that as chairman of the technical committee he had the responsibility for assessing the project and that his recommendation was mostly binding on the technical side. He states that there were serious concerns about the project, including P&ID’s lack of a track record in this area, its failure to respond to the availability of wet gas for the project, which had not been properly investigated by the time the GSPA was executed (which the technical committee learnt about only after the event). Throughout the process the contract was withheld from the Minister responsible for gas resources, Mr Odein Ajumogobia. In approving the project, the committee overlooked the deficiencies because of Dr Lukman’s direction.

137. Mr Tijani adds that shortly after the GSPA was signed there was a meeting to discuss gas flaring issues in the Calabar region but nobody at the meeting was aware that a contract for a gas processing plant in the area had been signed and Dr Lukman kept silent about it.

138. In his statement, Mr Tijani confirms the bribes outlined earlier in the judgment. The payment of US$30,000 to Conserve Oil on 17 October 2013 was intended for him personally; the two payments of NGN 3,440,000 and NGN 4,350,000 on 3 April 2014 from Lurgi and Conserve Oil were intended as P&ID’s contributions to his son’s wedding (the second being funded out of an earlier payment by Lurgi to Conserve Oil on 10 March 2014).

139. Mr Tijani says that none of these payments were for services rendered by Conserve Oil in connection with the “Bonga Audit” project. He was not involved with that project beyond making the initial recommendation of Conserve Oil, the company of his close friend from childhood, Mr Tunde Odebunmi. It was only later when he retired from his post as the Lagos State Energy and Mineral Resources Commissioner in May 2015 that he acquired an interest in Conserve Oil.

In his first statement he accepts at paragraph 50 that the costs sunk in the preparatory work, referred to in paragraph 47 of Mr Quinn’s statement, were funded by Tita-Kuru. However, because Nigeria never challenged that part of Mr Quinn’s evidence it was not a contentious issue in the arbitration. As regards finance for the GSPA, Mr Cahill states at paragraph 80:

“It was never intended that the finance for the entire project would come from spare cash which [Mr Quinn] and I might have…we intended to fund the project with our own money to the point at which it became bankable, and thereafter we would raise finances…P&ID had been incorporated in the BVI in part to be an entity which would be attractive to lenders – a ‘bankable’ proposition. We were comfortable with the notion that the General [Danjuma] might be the source of such funding, but we were also nurturing interest from our discussions with other potential funders.”

Mr Cahill’s statements

140. Mr Cahill was Mr Quinn’s business partner and co-founder of P&ID. For the purposes of the proceedings before the court Mr Cahill has given two statements. He denies that the GSPA or the Awards were procured by fraud, corruption or other illegal conduct.

141. In his first statement he accepts at paragraph 50 that the costs sunk in the preparatory work, referred to in paragraph 47 of Mr Quinn’s statement, were funded by Tita-Kuru. However, because Nigeria never challenged that part of Mr Quinn’s evidence it was not a contentious issue in the arbitration. As regards finance for the GSPA, Mr Cahill states at paragraph 80:

“It was never intended that the finance for the entire project would come from spare cash which [Mr Quinn] and I might have…we intended to fund the project with our own money to the point at which it became bankable, and thereafter we would raise finances…P&ID had been incorporated in the BVI in part to be an entity which would be attractive to lenders – a ‘bankable’ proposition. We were comfortable with the notion that the General [Danjuma] might be the source of such funding, but we were also nurturing interest from our discussions with other potential funders.”

142. In his second statement, Mr Cahill adds that when Mr Quinn said in his witness statement for the arbitration that the Cross River State Government had approved the land for the GSPA plant, that was accurate; Mr Quinn had not said that P&ID had bought the land.

143. Regarding the payments which Nigeria says are bribes, Mr Cahill says in his first statement that Mr Quinn and he became friendly with Ms Taiga when she was in the Defence ministry. He knew nothing about the deposit of US$10,400 in her bank account in August 2010. After she retired as a civil servant, Mr Cahill said, she would telephone him during Mr Quinn’s long illness and he was happy to provide her with support.

Regarding the payments which Nigeria says are bribes, Mr Cahill says in his first statement that Mr Quinn and he became friendly with Ms Taiga when she was in the Defence ministry. He knew nothing about the deposit of US$10,400 in her bank account in August 2010. After she retired as a civil servant, Mr Cahill said, she would telephone him during Mr Quinn’s long illness and he was happy to provide her with support.

144. Mr Cahill states that he arranged for Ms Taiga to receive US$1000 through one of his companies, Eastwise Trading Ltd in September 2015. When she had a bad fall in late 2017, he made two payments through ICIL, each of US$10,000, on 18 December 2017 and 27 June 2018. They were not large amounts to him and intended for an old friend needing to meet medical needs. There were two further payments of US$500 each in March 2019, which his (Mr Cahill’s) assistant made, possibly for medical expenses. Mr Cahill adds that he provided further (unspecified) assistance to Ms Taiga for legal and other expenses after her release from arrest in September 2019.

145. In his first statement Mr Cahill denies the “black bag” cash payment of US$50,000 to Mr Tijani allegedly made in April 2009. Further, he adds, Mr Tijani was not remotely critical to obtaining the GSPA. As to the payments to Mr Tijani and Conserve Oil, these were for the services provided to Lurgi in obtaining technical personnel for the “Bonga Audit” project in 2013. Payment had been made of US$30,000 in October 2013 from another company he controlled, SESFTF Progress Ltd, since Lurgi had a joint account and payment (which Mr Tijani was insisting on) might be delayed. The Bonga Audit work was completed by the end of 2014.

146. In his second statement, Mr Cahill says that they chose Mr Tijani to assist with the Bonga Audit given his former membership of the technical committee of the Ministry and his extensive experience in the petroleum industry. The payment of N4,350,000 in March 2014 was to Conserve Oil for services rendered; he did not know whether it was then paid to Mr Tijani, although it would not surprise him since Conserve Oil was his company. Mr Cahill cannot recall the two payments of some US$30,000 made to Mr Tijani personally on 3 April 2014 and 22 April 2015, but he had no doubt that they were for Bonga Audit work and it was entirely possible that they were bonus payments.

147. As for the payments to Ms Taiga’s daughter of US$4,969.50 and US$5,000 in December 2009 and January 2012, which the Nigerian authorities had recently learnt about in the US, he had been told by someone working for ICIL at the time that he recalled they would be to help Ms Taiga with her medical expenses. They would have been authorised by Mr Quinn, who was the type of person who would always want to assist a friend.

148. The payment to Mr Dikko, explains Mr Cahill, would have been Mr Quinn’s home- town pride, with the IBA conference occurring in Dublin.

149. Mr Cahill explains in his second statement that during the negotiation process of the GSPA, in response to inquiries about progress, government officials would occasionally provide an update and from time to time documents. That included Dr

Ibrahim, who was the likely source of an internal Ministry memorandum referred to in Mr Quinn’s witness statement for the arbitration.

Mr Nolan

150. Mr Nolan has worked with Messrs Quinn and Cahill for many years. In his first statement he attributes the spikes in ICIL’s cash withdrawals in 2008 and 2010 to Nigeria being a cash economy and to the need for cash for foreign exchange transactions on the parallel market. He also refers to cash being required for salaries, contractor payments, accommodation, travel and so on in relation to ICIL’s various projects in Nigeria.

Ramatu Lukman

151. Ramatu Lukman is the daughter of Dr Lukman, who was Minister of Petroleum Resources at the time of the GSPA and who died in 2014. She refers to Dr Lukman’s distinguished career, both in Nigeria and internationally. She states that he was a devoted public servant, of the highest integrity and would never have taken a bribe. As to the deposits of US$10,000 in 2009 in the GT Bank accounts, she says that may have been her father bringing relatively modest amounts of cash into Nigeria, as he was permitted to do, to help with the costs of living when he was there.

Legal framework

Position prior to award

152. Section 73 of the 1996 Act governs the position before an award is published: it has no relevance to the conduct of the party from that moment onwards: Merkin and Flannery on the Arbitration Act 1996 (6th edn) at [73.7]. Under it parties lose their right to object to a serious irregularity like fraud unless they raise the matter “forthwith” and can show that, at the time they took part or continued to take part in the proceedings, they did not know and could not with reasonable diligence have discovered the grounds for their objection.

153. In Sumakan Ltd v Commonwealth Secretariat [2007] EWCA Civ 1148, [2008] 2 All ER (Comm) 175 the Court of Appeal agreed with Toulson J that it was wrong to construe section 73 to hold that a person could with reasonable diligence have discovered facts which it neither knew nor believed nor had grounds to suspect: [36], [38], [62].

Extending time and the Kalmneft factors

154. Section 70(3) of the 1996 Act applies a 28 day time limit to an application or appeal under sections 67, 68 or 69. As a result of section 80(5) the court has discretion to extend the time limit. Colman J considered the background to this discretion in AOOT Kalmneft v Glencore [2001] 2 All E.R. (Comm) 577, [2002] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 128 – a case of an alleged procedural irregularity – and continued:

“[59] Accordingly, although each case terms on its own facts, the following considerations are, in my judgment, likely to be material:

(i) the length of the delay;

(ii) whether, in permitting the time limit to expire and the subsequent delay to occur, the party was acting reasonably in all the circumstances;

(iii) whether the respondent to the application or the arbitrator caused or contributed to the delay;

(iv) whether the respondent to the application would by reason of the delay suffer irremediable prejudice in addition to the mere loss of time if the application were permitted to proceed;

(v) whether the arbitration has continued during the period of delay and, if so, what impact on the progress of the arbitration or the costs incurred in respect of the determination of the application by the court might now have.

(vi) the strength of the application;

(vii) whether in the broadest sense it would be unfair to the applicant for him to be denied the opportunity of having the application determined.”

The Kalmneft factors and (i)-(iii) as primary factors

155. Later courts have regularly applied the so-called Kalmneft factors. In Terna Bahrain Holding Company WLL v Bin Kamil Al Shamsi [2012] EWHC 3283 (Comm), [2013] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 86 Popplewell J stated them in a slightly refined form ([27]) and some courts have used these. The Kalmneft factors have been regarded as exhausting the considerations bearing on the exercise of the discretion to extend time.

156. In Nagusina Naviera v Allied Maritime Inc [2002] EWCA Civ 1147, [2003] 2 CLC 1, the Court of Appeal held that a judge’s exercise of discretion refusing to extend the time for service of an arbitration appeal under section 1(2) of the Arbitration Act 1979 could not be faulted. One of the submissions the court considered was that, although made under different provisions, the judge had not considered all the Kalmneft factors. At paragraph [39] Mance LJ (with whom Simon Brown and Latham LJJ agreed) said the judge had well in mind as primary factors those which in Kalmneft were factors (i)– (iii).

157. In his discussion of what in Kalmneft is factor (vi), Mance LJ thought it material that the case was not one where the appellants’ challenge was “so strong that it would obviously be a hardship for them not to be able to pursue it”: [41]. As to factor (vii), he said that considerations of overall justice and fairness had always to be viewed in the particular context that Parliament and the courts had repeatedly emphasised the importance of finality and time limits for any court intervention in the arbitration process: [42].