Posted by By Craig Timberg on

Police call it "a kola nut." Journalists call it "the brown envelope." And politicians call it "a welfare package." Whatever the name, the almighty bribe long has lubricated Nigerian society as it has few others on Earth.

ABUJA, Nigeria -- Police call it "a kola nut." Journalists call it "the brown envelope." And politicians call it "a welfare package." Whatever the name, the almighty bribe long has lubricated Nigerian society as it has few others on Earth.

Corruption is so rampant that when the nation's education minister, Fabian Osuji, was caught giving $400,000 to Nigerian lawmakers for favorable votes, he formally protested that such behavior was "common knowledge and practice at all levels of government." Besides, Osuji added, he had struck a good deal; the lawmakers had asked for twice as much. He was fired from the government.

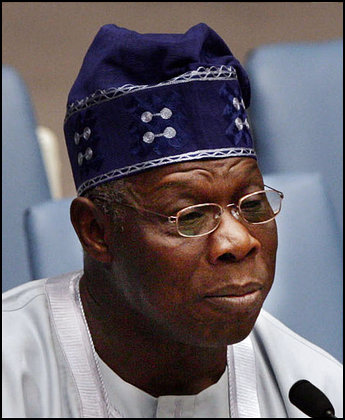

Now, after decades of open and freewheeling graft, President Olusegun Obasanjo has declared war on corruption. And Osuji is far from alone in suddenly having to account for his actions.

A succession of senior government figures -- including the top police official, the housing minister and the Senate president -- also have been pushed from their jobs in recent months and threatened with jail for offenses that once would have earned them little more than a wink.

The police official, Tafa Balogun, even appeared in court wearing handcuffs. And in separate action, a court in Abuja, the capital, has ruled that the son of late dictator Sani Abacha must stand trial for his alleged role in the looting of more than $1 billion in public funds during his father's reign from 1993 to 1998.

Obasanjo and his allies portray the anti-corruption campaign as nothing less than a battle to redeem the tainted soul of a nation, the largest in Africa with about 137 million people. Even the Catholic Mass here includes a prayer against corruption.

"We are trying to change Nigeria," said Mustapha Akanbi, a stern retired judge who heads one of two independent anti-corruption commissions and who, on his desk, has a paper clip dispenser that says: "Don't Give Bribe, Don't Take Bribe."

Akanbi said he tells his roughly 150 investigators and prosecutors that "they are engaged in a struggle, in a revolution for their country. We are trying to teach people to give up their greed and corruption and put service to the nation first."

Transparency International, a corruption monitoring group based in Berlin, ranks Nigeria as the third-most-corrupt nation on Earth -- a fact that has prompted some here to joke that a clever government official must have paid a hefty bribe to keep the group from ranking Nigeria first or second. Only Bangladesh and Haiti were rated more corrupt.

Navigating the most basic government services, such as getting freight through customs, often requires a bribe in Nigeria. Motorists have little choice but to pay police officers -- many armed with automatic rifles -- who set up impromptu roadblocks to demand a "kola nut." The caffeine-laden nut is a traditional offering of hospitality in Nigeria, but to police the term refers to a wad of money worth anywhere from a few cents to several dollars, depending on the type of vehicle and the mood of the officer.

Politicians take bribes and give them, including payments to reporters who can make more money from those they cover than from their meager newspaper paychecks, according to journalists familiar with the practice.

For the high-stakes deals between politicians, the preferred packages are known as "Ghana-Must-Go bags." The satchels, made of colorful woven plastic, were commonly used as suitcases in the 1980s, when the government was pressuring immigrants from nearby Ghana to return home. Filled, a Ghana-Must-Go bag can hold hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of naira, the Nigerian currency.

It was such a bag, according to news reports here, that the education minister used in December to send a "welfare package" to the home of the Senate president. "I protested this demand," Osuji told an ethics committee, "but the Senate president sternly told me to go back to my ministry and find the money."

Many here trace the root of corruption to the decades of military governments that ruled Nigeria before Obasanjo's election in 1999. The treasury, flush with money from some of the world's most productive oil fields, became a personal bank account for a succession of generals. The rot oozed down to lawmakers, governors and judges, say Nigerian officials. Civil servants, who in some cases went months or years without receiving their salaries, collected what they could by selling their services.

Corruption has grown so severe that many here fear it has become a deterrent to investors and, worse still, a reason for international leaders not to forgive Nigeria's crushing foreign debt of $35 billion.

In an address to the nation in March, Obasanjo warned that corruption "contaminates collective morality and values" and tarnishes the image of Nigeria in the eyes of the world. "This is a warning to all those who have tendencies to be corrupt," he said. "This administration is fully poised to deal ruthlessly with corruption in all its ramifications."

Many Nigerians dismiss Obasanjo's anti-corruption campaign as an elaborate form of public relations to win concessions from lenders and burnish the president's reputation as a world leader. Critics note that only now, six years after Obasanjo first won office promising to crack down on corruption, are any major figures being brought to justice, and none has gone to jail.

Political opponents also contend that the president's election victories in 1999 and 2003 were so brazenly rigged that he lacks the moral authority to attack corruption.

"It is still too early to start clapping," said Ibrahim Modibbo, spokesman for the main opposition party here, the All Nigeria People's Party. "We strongly believe the whole thing is a smoke screen."

Efforts to stem corruption began making headlines in August 2003 when Nasir Ahmad el-Rufa'i, who had just been named to a ministerial post overseeing the capital region, announced that two senators had asked him for bribes to facilitate his confirmation. According to el-Rufa'i, one of the two senators told him he needed 55 votes, which would cost him 54 million naira, or roughly $415 -- 1 million naira each for 54 senators but nothing for himself. He was such an admirer of the nominee, he said, that his vote was free.

Both men named by el-Rufa'i have denied his allegations and been cleared of wrongdoing by a legislative committee. El-Rufa'i won confirmation anyway, and he has since become an outspoken symbol and advocate of the anti-corruption campaign.

In a recent interview, el-Rufa'i estimated that at least three out of every four lawmakers are corrupt, as are more than half of the nation's governors and many of its civil servants. Most of the cabinet ministers and the nation's top judges are clean, he said, but in the lower levels of the judiciary, bribery is more common.

He maintained, however, that Nigeria is beginning to change, if only because corrupt government officials have begun to fear that they might get caught -- and punished.

"We are moving away from a culture of impunity, where people felt they could be corrupt and get away with it, to the point where people are scared of being corrupt," el-Rufa'i said. "If a few more ministers go to jail, if a few more members of the National Assembly go to jail, believe me, people will line up and do the right thing."